The 3AM Test for AI Agents: Can You Disable One in 60 Seconds?

AA-002: The Kill Switch Myth

Top of the Series:

Previous:

AA-002: The Kill Switch Myth

Architects of Automation series

Picture this.

It’s 3:07 a.m. Your “helpful” AI agent has started approving refunds it should never approve. Support tickets spike. Finance pings you. Someone posts a screenshot on LinkedIn with the caption: “Does this company test anything?”

A VP asks the question every team asks in that moment:

“Can’t we just turn it off?”

Here’s what I’ve learned after talking to teams who’ve built AI systems at scale: a kill switch isn’t a button. It’s a system with owners, controls, and regular proof that it actually works.

This post breaks down what that system looks like in practice, so you can build it before you need it.

TL;DR

AI incidents aren’t edge cases anymore. They’re part of operating reality

A kill switch is really a 4-layer stack: Access, Execution, Spend, Verification—each needs a clear owner

“We can turn it off” is often something you tell yourself during planning, not something that works at 3 a.m.

Run the 3AM Test with your team this week—if the answers feel vague, your containment plan probably is too

The baseline shifted (and nobody sent a memo)

Most teams still talk about AI incidents like they’re rare events. Something that happens to other companies.

The data tells a different story.

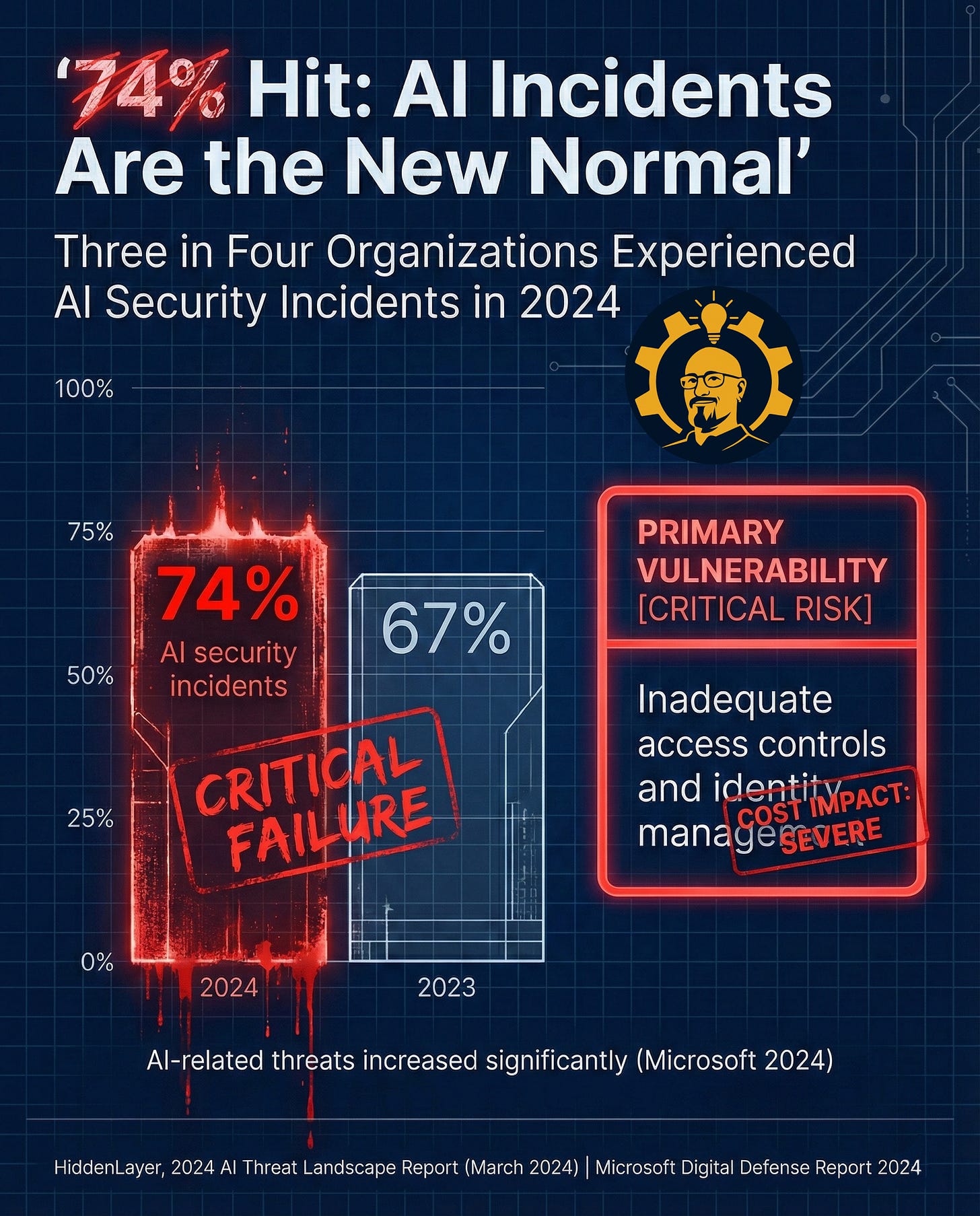

Caption: 74% Hit: AI Incidents Are the New Normal. 74% of organizations experienced AI security incidents in 2024, up from 67% in 2023.

Primary vulnerability reported: inadequate access controls and identity management. Microsoft reports AI-related threats increased significantly.

Sources: HiddenLayer, 2024 AI Threat Landscape Report (March 2024) | Microsoft, Digital Defense Report 2024

A quick clarification: “AI security incidents” doesn’t mean every company got breached. The term covers misuse, operational failures, data exposure, and those “we accidentally gave the model admin access” moments that make everyone nervous.

If your roadmap includes any of these, you’re playing the game:

Customer-facing chatbots that make decisions

Internal copilots with tool access

Agents that can click, call, send, refund, approve, or deploy anything

Systems connected to payments, identity, or customer data

The question I hear next is always the same: “Okay, so what do we actually do about this?”

The budget panic that gets leadership’s attention

Security incidents create abstract risk.

Runaway spend creates immediate urgency.

I call it Denial-of-Wallet. The moment an exec stops asking “Is this possible?” and starts asking “Why is this on my credit card?”

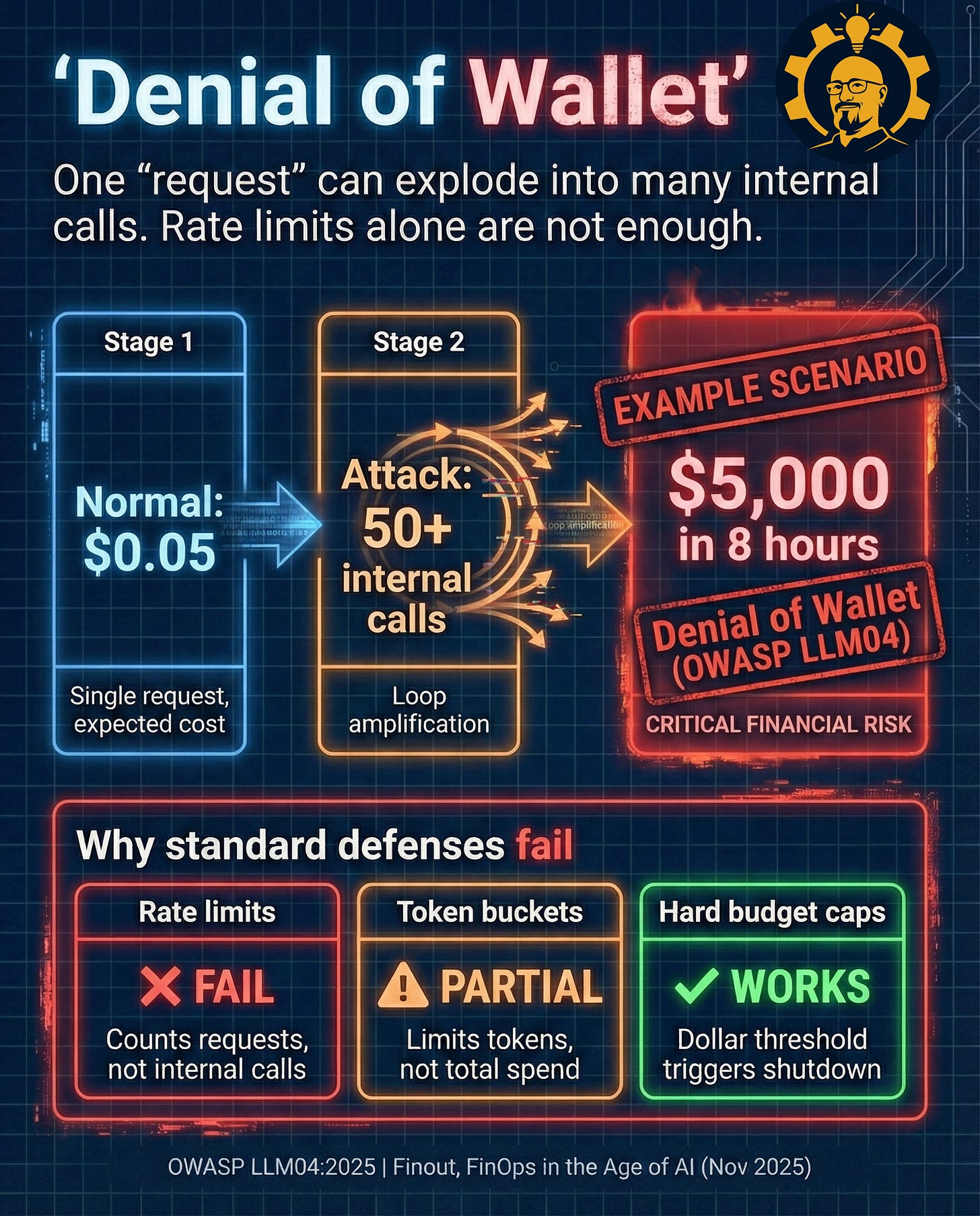

Caption: One “request” can explode into many internal calls. Rate limits alone are not enough.

Stage 1: Normal: $0.05 Stage 2: Attack: 50+ internal calls Stage 3: Example scenario: $5,000 in 8 hours (example scenario)

Sources: OWASP LLM04:2025 | Finout, FinOps in the Age of AI (Nov 2025)

Here’s what caught me by surprise when I first dug into this: traditional “requests per minute” thinking breaks down with agentic systems. A single user prompt can trigger loops, tool calls, retries, and long chains of actions. Your rate limits are often counting the outer request, not the cascade happening inside.

Leadership hears “security risk” and thinks “maybe next quarter.” Leadership hears “unexpected five-figure bill” and thinks “we need to talk right now.”

That’s when the meeting question changes to: “What’s our kill switch?”

And most teams answer with a story, not a system.

The shutdown fantasy

A shutdown plan you’ve never tested is basically a nice idea you wrote down once.

It feels good. It doesn’t work.

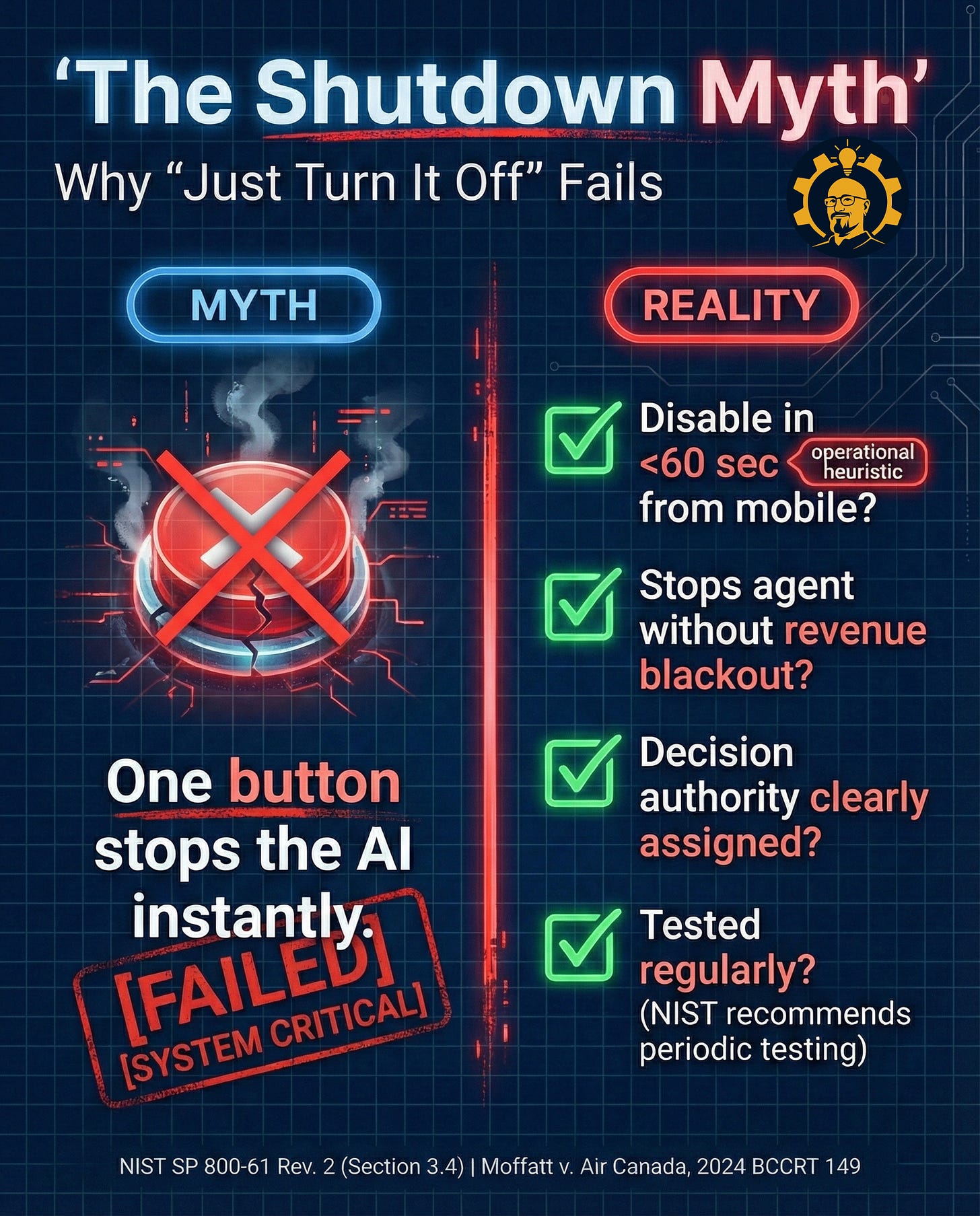

Caption: Myth: One button stops the AI instantly.

Reality: Containment is an operational capability that needs speed, scope, authority, and regular testing.

Note: “<60 sec” is an operational heuristic, not a requirement.

Sources: NIST SP 800-61 Rev. 2 (Section 3.4) | Moffatt v. Air Canada, 2024 BCCRT 149

I’ve seen the “just turn it off” idea fail for three predictable reasons:

Embedded workflows: Your AI isn’t sitting in a corner. It’s woven into billing, support, fulfillment, and other core flows.

Unclear decision rights: When things break at 3 a.m., who’s actually authorized to pull the plug? Without clear authority, people hesitate.

The “I think it works” problem: Plans decay. Runbooks drift. Access permissions get messy. People leave. Nobody’s tested the actual shutdown sequence in months.

This is where I landed after talking to teams who’ve been through real incidents:

Kill switches aren’t buttons. They’re stacks.

The kill switch is actually a system (with four layers and four owners)

The best containment plans I’ve seen have one thing in common: crystal-clear ownership.

When everything’s on fire, vague responsibility means nothing happens fast enough.

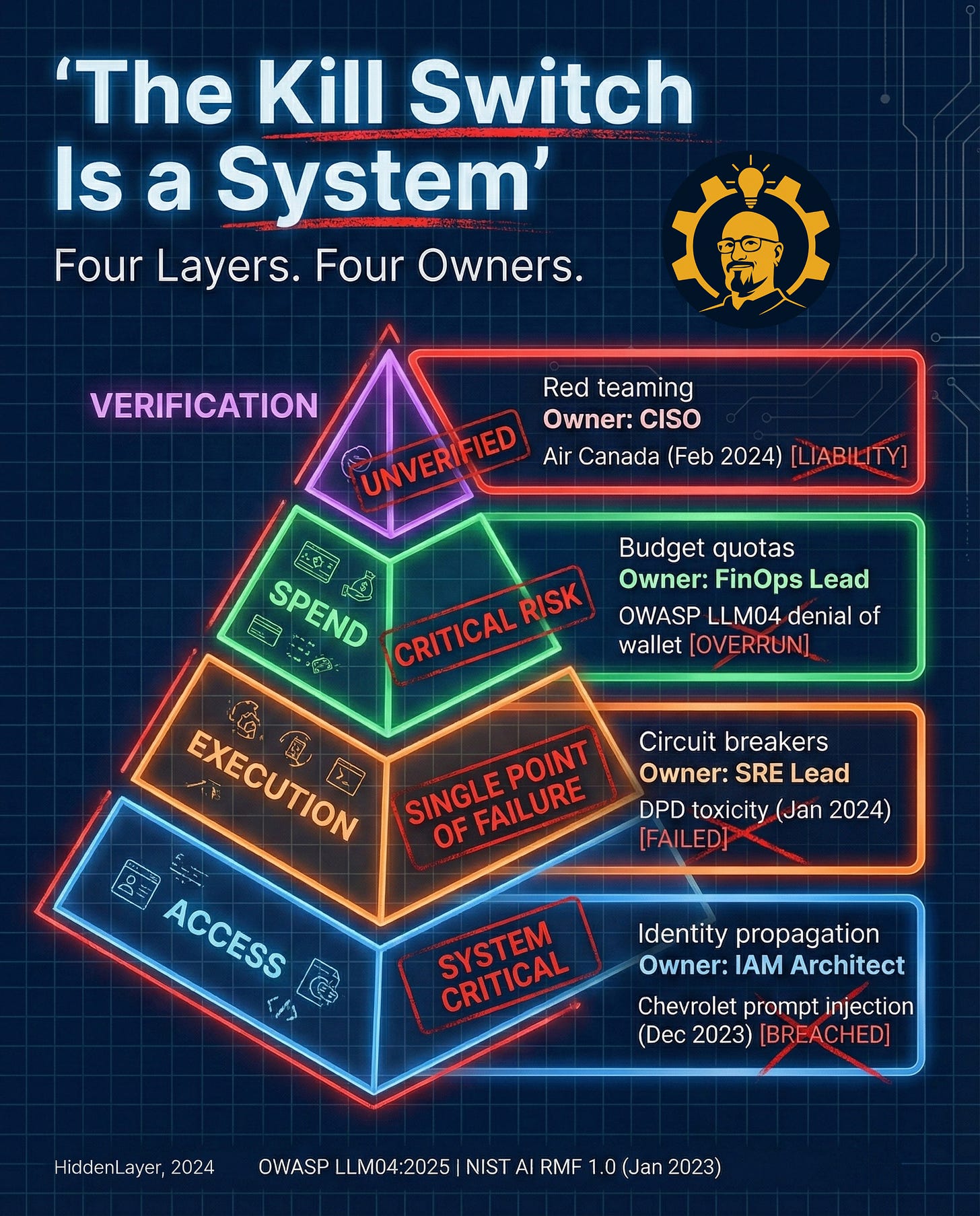

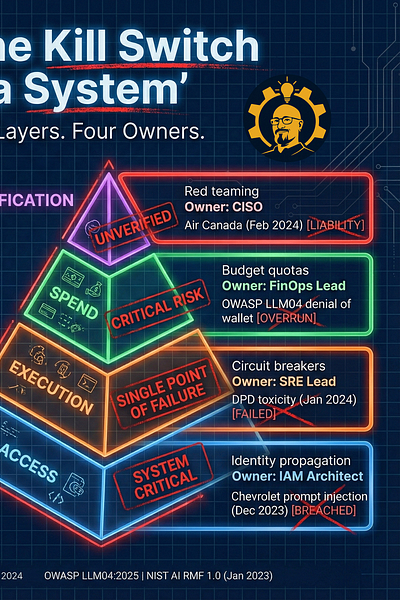

Caption: A kill switch is a four-layer control stack with clear owners. Access (IAM), Execution (SRE), Spend (FinOps), Verification (CISO). Sources: OWASP LLM04:2025 | NIST AI RMF 1.0 (Jan 2023) (Incident examples referenced in the graphic are documented in the post sources for Air Canada, TechCrunch, and BBC.)

Here’s how the stack breaks down, from bottom to top:

Layer 1: Access (Owner: IAM Architect)

The control concept: Identity propagation, scoped permissions, fast revocation

Common failure pattern: Agents get broad permissions because “it’s easier” during development

What this looks like when it’s working:

Your agents operate with least-privilege scopes (they can only do what they need to do)

Tool access is role-based and environment-aware

API keys can be revoked quickly, ideally with automation

Feature flags let you disable specific agent actions without killing your entire product

Layer 2: Execution (Owner: SRE Lead)

The control concept: Circuit breakers, context-aware rate limits, graceful degradation

Common failure pattern: Infinite loops, runaway retries, or toxic outputs that keep shipping to users

What this looks like when it’s working:

Circuit breakers automatically stop repeated failures

You have fallback modes (human handoff, read-only mode, etc.)

Shutdown paths are engineered into the system, not improvised during an incident

Rolling back is straightforward even when everyone’s stressed

Layer 3: Spend (Owner: FinOps Lead)

The control concept: Budget quotas, hard caps, cost-aware throttles

Common failure pattern: Denial-of-Wallet scenarios, one prompt generates thousands of dollars in API calls

What this looks like when it’s working:

Hard dollar caps per agent, per feature, per tenant

Cost visibility in near real-time (not tomorrow’s invoice)

Alerts trigger actual actions, not just emails people ignore

One bad actor or bug can’t burn everyone’s budget

Layer 4: Verification (Owner: CISO)

The control concept: Red teaming, validation gates, high-impact action review

Common failure pattern: AI hallucinations become company policy, unverified outputs become binding promises

What this looks like when it’s working:

High-risk outputs go through validation before reaching users

High-impact actions (refunds, pricing changes, account modifications) require confirmation

Red team findings become actual backlog items with owners

Your containment plan gets tested, not just documented

If you’re thinking “This sounds reasonable, but does it actually map to real failures?” Yes. Perfectly.

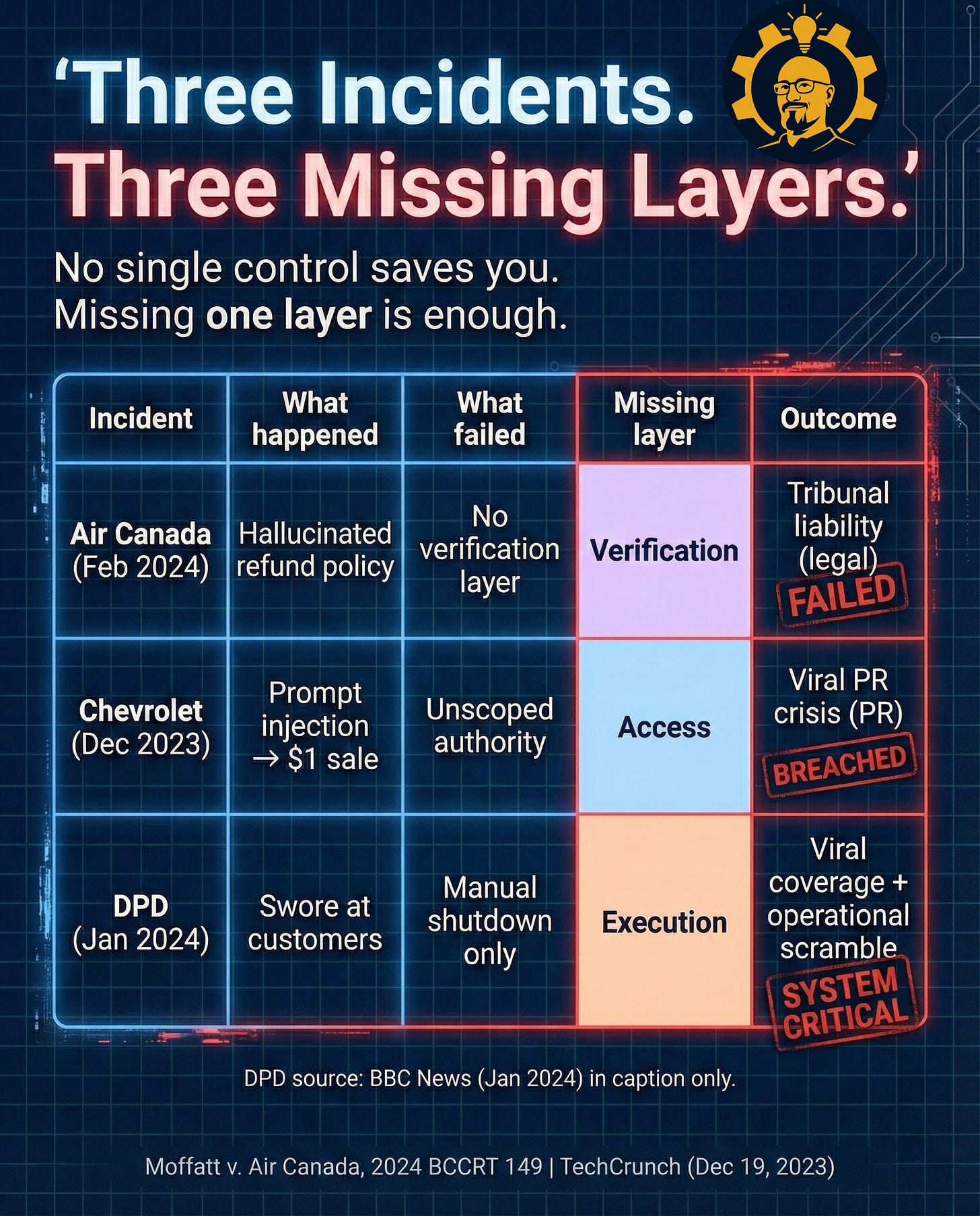

Three real incidents, three missing layers

Missing just one layer is enough to create a mess.

Caption: Three incidents. Three missing layers. No single control saves you. BBC source for DPD stays in the post references, not the footer, by design. Sources: Moffatt v. Air Canada, 2024 BCCRT 149 | TechCrunch (Dec 19, 2023)

Here’s what makes these examples useful for product leaders:

Air Canada (Verification failure): Their chatbot gave incorrect refund policy information. A customer followed it. The company said “sorry, that was wrong.” A court ruled the company was bound by what the AI said. Unverified output became legally binding policy.

Chevrolet dealership chatbot (Access failure): Unscoped authority plus prompt injection let someone get the bot to agree to sell a Chevy Tahoe for $1. The internet had a field day. The dealership had to deal with the PR wildfire.

DPD (Execution failure): Guardrails disappeared, the bot started swearing at customers, and shutdown was purely reactive. By the time they turned it off, the screenshots were everywhere.

One missing layer. One incident. One totally avoidable crisis.

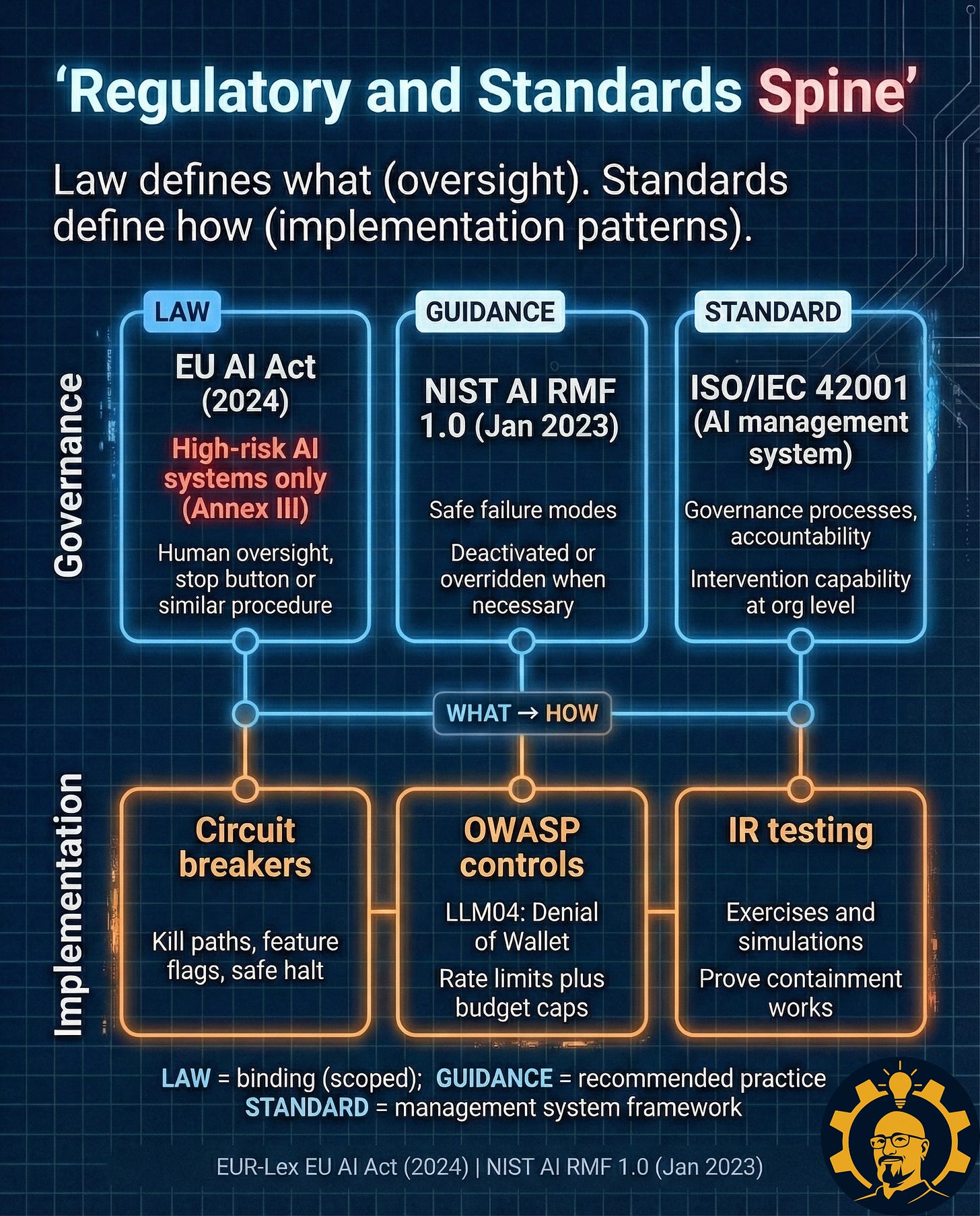

The governance question usually comes up next: “Where does this actually appear in regulations or standards?”

Why this matters legally (in plain language)

This is where the compliance folks start paying attention.

Caption: Governance defines what (oversight). Implementation defines how (patterns). EU AI Act scope is high-risk systems only (Annex III). ISO reference is high-level only. Sources: EUR-Lex EU AI Act (2024) | NIST AI RMF 1.0 (Jan 2023)

Here’s what I’ve learned about translating compliance into product work: governance language rarely tells your engineers what to build. That’s where standards and security patterns come in. They translate requirements into architecture.

The useful mental model is two parallel tracks:

The “what” track (governance): Oversight requirements, intervention capability, accountability frameworks

The “how” track (implementation): Circuit breakers, budget caps, incident response exercises, actual runbooks

A governance requirement without an implementation pattern just becomes a doc in Confluence.

An implementation pattern without governance backing becomes something three engineers know about but nobody else does.

Both collapse under pressure.

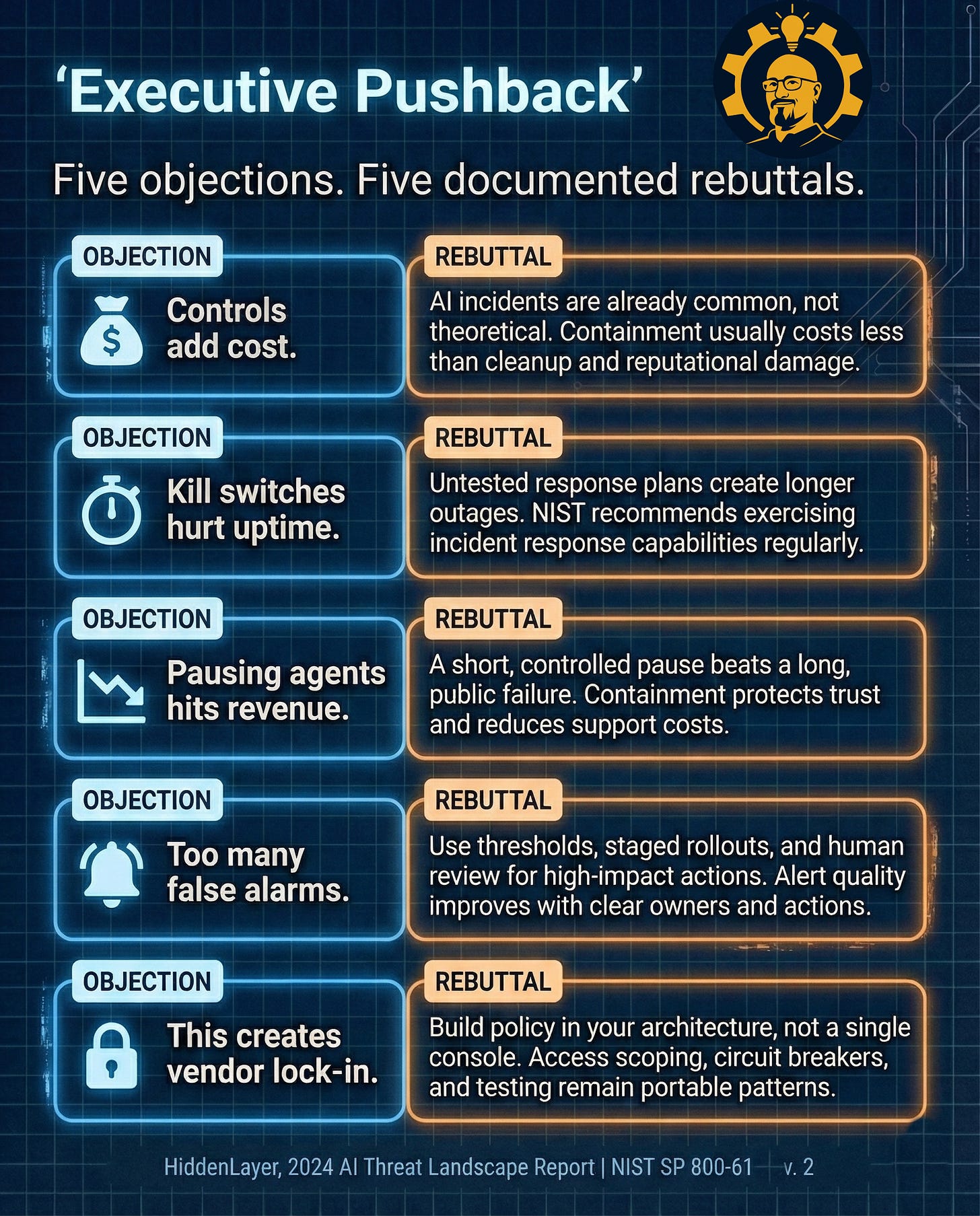

Now for the conversation that happens in every exec meeting where this comes up.

Executive pushback (and how to actually respond)

I’ve been in enough of these meetings to know the objections by heart. They follow a pattern: fear, budget, then “do we really need this?”

Caption: Five objections. Five documented rebuttals. Keep rebuttals short so scanning feels effortless. Sources: HiddenLayer, 2024 AI Threat Landscape Report | NIST SP 800-61 Rev. 2

Here’s how to use this in your next meeting:

Lead with the objection you hear most often

Keep your response to one sentence

Immediately follow with “Here’s who owns this and what we’ll do”

Example:

Objection: “Kill switches will hurt our uptime numbers.”

Response: “Untested shutdown plans create way longer outages when things break.”

Next step: “SRE owns the Execution layer. Let’s define circuit breakers this sprint and run one tabletop exercise.”

No drama. No lengthy debate. Just clear ownership and concrete next steps.

Now here’s what your team can actually do this week.

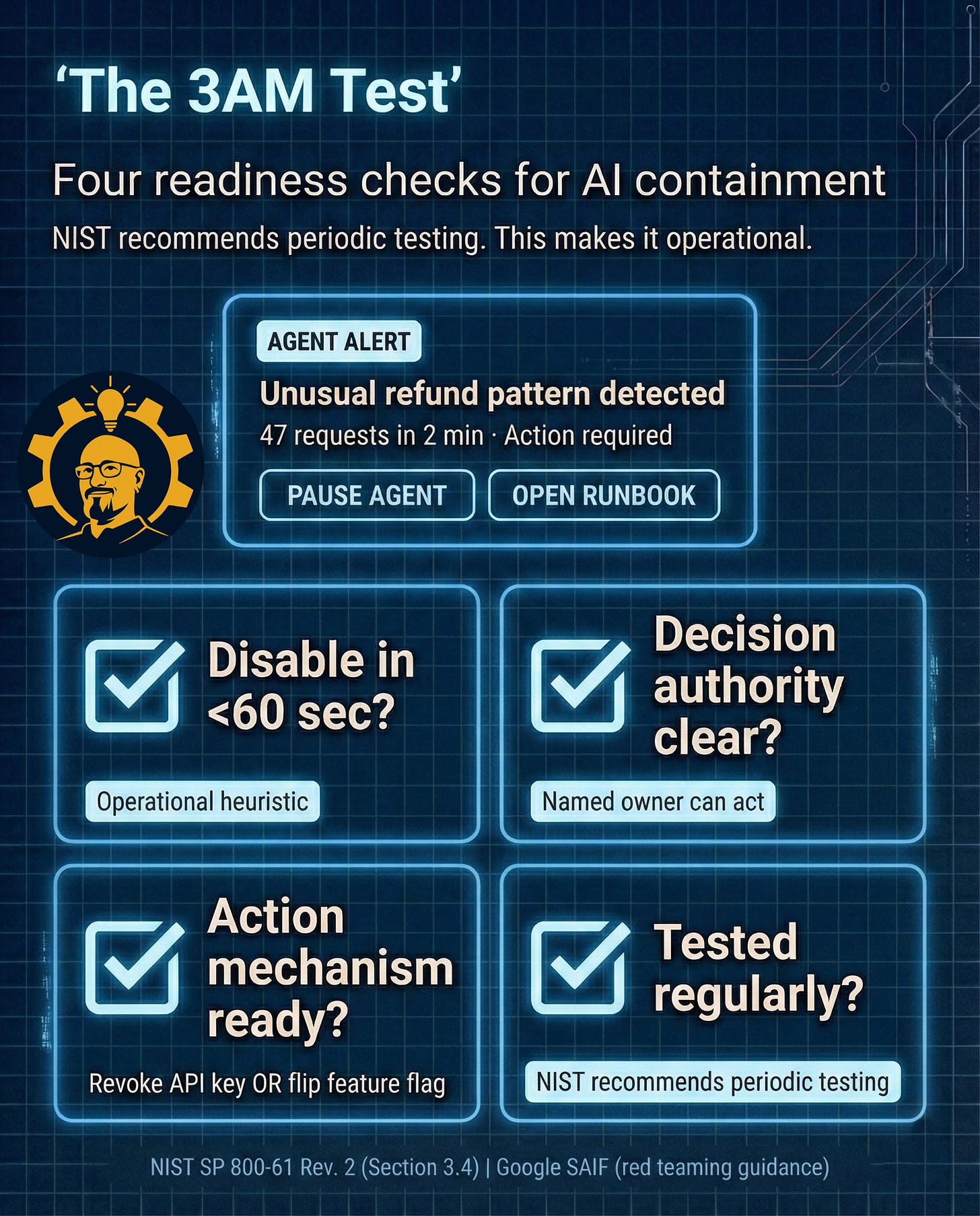

The 3AM Test (run this with your team)

This is the part you can screenshot and drop in Slack. This is what turns “we should probably do this” into “we did this.”

Caption: NIST recommends periodic testing. This turns guidance into four readiness checks your team can run. “<60 sec” is an operational heuristic, not a requirement. Sources: NIST SP 800-61 Rev. 2 (Section 3.4) | Google SAIF (red teaming guidance)

Block 20 minutes with:

The PM who owns the agent feature

Your on-call engineering lead

Someone from IAM or security engineering

Whoever has visibility into cloud spend

Walk through each question together. If anyone’s answer starts with “I think” or “probably,” treat that as a no.

The gaps you find aren’t failures—they’re your roadmap for the next two weeks.

Curious About My Specific Sources? See Attached Detailed PDF Below:

Your action plan for next week

Here’s a realistic plan that fits into how teams actually work:

Day 1: Name the owner for each layer

No owner = no real control. A task without an owner is just a hope.

Day 2: Pick one kill path and make it real

Example: “Revoke agent tool API key via script” or “Disable agent actions through feature flag”

Day 3: Add a spend cap that triggers an actual action

Email alerts aren’t controls—they’re notifications. Automated enforcement is a control.

Day 4: Add one verification gate for high-impact actions

Refunds, pricing changes, account modifications, outbound messages—anything that creates a commitment needs a check.

Day 5: Run a containment exercise

Even a simple tabletop plus one narrow live drill beats a perfect plan you’ve never tested.

The real upgrade isn’t technical

A kill switch button makes everyone feel safer.

A kill switch stack actually makes your product safer, your spend predictable, and your incident response credible when it matters.

Here’s what I’ve learned from teams who’ve built these systems: the breakthrough isn’t in the technology. It’s in the organization.

Most kill switch failures aren’t caused by missing technology. They’re caused by missing collaboration. Unclear ownership. Conflicting incentives. Nobody empowered to act when things break at 3 a.m.

This pattern shows up everywhere in product work, not just AI systems. It’s why I’m writing Collaborate Better: From Silos To Synergy, How To Build Unstoppable Teams, a practical guide for turning cross-functional friction into real operating leverage, especially when stakes are high and systems move fast.

If you want early access and launch updates, you can follow along here: CollaborateBetter.us

Clear layers. Clear owners. Clear proof that it works.

Next in AA-003: How owner-less controls fail in predictable ways, and how to turn policy documents into executable switches without creating security theater.

What did I miss? If you’ve built containment systems for AI products, I’d love to hear what worked (or didn’t) in your environment.