Resistance Files: 📺 The Rabbit-Ear Caper ⚡

Case File #006

Top of the Series: Resistance Files: The Unusual Suspects

Previous: 🎬 Resistance Files: Red Envelope Rendezvous

Resistance Files: The Broadcast Job

Case File No. 006 — Television

Moving pictures no one thought anyone would sit and watch.

The Flicker in the Dark

The detective’s office glows with the faint light of a cathode ray tube.

The static that once whispered secrets now paints shadows on the wall.

They said no one would sit still for it.

They said motion was for theaters, not living rooms.

But the moment the picture moved, so did history.

“Every signal starts as static. Every revolution begins with a flicker.”

The Crime Scene

They said it was a parlor trick.

A ghost in a box.

A rich man’s hobby that would fade once the novelty burned out.

In the smoky workshops of the 1920s, strange light bled through hand-built screens.

Blurry silhouettes danced in grainy silence, faces forming and dissolving like spirits caught between worlds.

To most, it looked like madness. To a few, it looked like the future trying to break through static.

John Logie Baird in London worked by lamplight, his lab full of wires, whirring fans, and the faint hum of obsession.

Across the ocean, a young Philo Farnsworth in Utah sketched diagrams in chalk, eyes wild with conviction that pictures could ride the same air as sound.

Both were dismissed as cranks, “tinkerers with too much imagination and too little sense.”

And then there was David Sarnoff of RCA — the king of radio, a man who could sell silence as a symphony.

He played both sides like a detective flipping witnesses.

He bankrolled experiments in television, but only enough to keep the competition close and the future on a leash.

The papers laughed.

“TELEVISION A NOVELTY, NOT A NECESSITY,” one headline declared, as if the truth could be printed fast enough to catch what was coming.

Critics asked the same smug question:

“Who would sit and stare at a box when you can listen while you work?”

But in the quiet corners of dusty labs, that question was already answering itself — one flicker at a time.

Every glow on every glass tube was a confession: the world was about to start watching.

The Suspects

Every crime has its lineup, and this one reads like a gallery of fear.

The Radio Giants — The first kings of the air, clutching their microphones like crowns, terrified that pictures would silence their golden voices.

The Print Barons — Ink-stained hands gripping columns and headlines, sneering at the thought that light and motion could outshine the written word.

The Government Men — Regulators with shaking hands, whispering about mass hypnosis, propaganda, and a public too easily persuaded by moving light.

And the People Themselves — The everyday skeptics. Housewives, soldiers, secretaries, all scoffing at the flicker. “Why sit still to stare at nothing?” they said — until nothing started staring back.

Each suspect shared the same alibi: tradition.

Each had the same motive: control.

Because every empire fears its successor,

especially when it arrives with a plug.

“Every empire fears its successor, especially when it comes with a plug.”

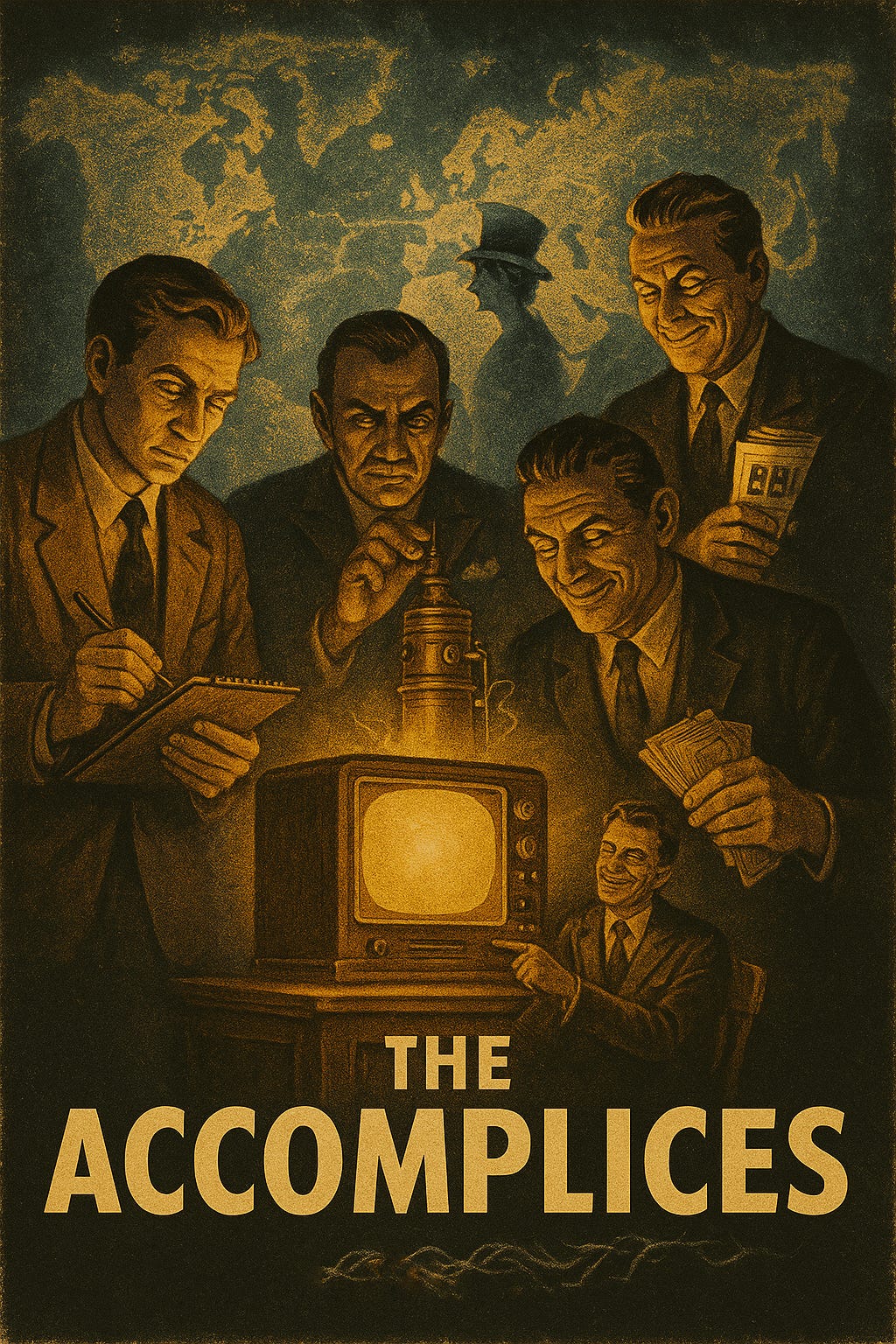

The Accomplices

No great caper unfolds without a crew.

Television wasn’t born from one genius in a lab coat — it was pieced together by rivals, dreamers, and double-crossers who mistook competition for progress.

First came Philo Farnsworth, the teenage prodigy from the Utah plains. He didn’t invent from theory — he invented from dirt. As he guided his plow through rows of wheat, he saw lines etched into the earth like the scan of an image. Years later, he’d recreate that vision inside a glass tube, calling it the image dissector. The world called it impossible — until it worked.

Then there was Vladimir Zworykin, an RCA engineer who played the game like a spy. He borrowed, copied, and “improved” whatever crossed his desk. Espionage was his art form, ambition his signature. He wasn’t just building a device — he was building a career out of other men’s blueprints.

And in the corner office above it all sat David Sarnoff, the mogul who smelled profit before anyone else could see it. He didn’t invent. He invested. He made sure RCA owned the air, the wires, and the story. For Sarnoff, invention wasn’t about vision — it was about jurisdiction.

Even the institutions joined the act.

The BBC in London and NBC in New York — both draped in public trust, both hungry for influence — began testing the flicker. They told themselves they were opening windows of knowledge, broadcasting enlightenment into every home.

But they weren’t opening windows.

They were unlocking doors.

And once the world stepped through, no one ever looked away again.

Exhibit F: The Picture That Wouldn’t Fade

They called it a miracle with knobs.

A flicker in a darkened hall at the 1939 World’s Fair — moving faces beamed through the air, shimmering like ghosts caught in glass.

The crowd gasped. For the first time, they weren’t reading history. They were watching it.

Farnsworth’s image dissector hummed quietly behind the curtain, its wires glowing like veins in a living thing. RCA’s engineers in crisp suits stood nearby, pretending not to sweat. And David Sarnoff, ever the showman, gave the pitch that would rewrite the century:

“Now, we add sight to sound.”

It was more than a slogan. It was a prophecy.

When war broke out, television went to the front lines.

The technology that once sold wonder began showing wreckage. Cities in flames. Soldiers marching. Families waiting. For the first time, the world didn’t just hear tragedy — it watched it happen in real time.

And when the soldiers came home, they didn’t leave the screens behind. They brought the glow with them, filled their living rooms with its hum, their nights with its company.

Every invention has its accomplice.

Sometimes it’s an idea.

Sometimes it’s an audience too spellbound to turn away.

Exhibit F: What Made Television Unstoppable? (Poll)

The picture’s clear, but the motive’s still in question.

So what really sealed the deal for television — the moment it stopped being novelty and became necessity?

👉 The Real Accomplice — What really made television unstoppable?

📺 The World’s Fair demo (1939)

⚙️ Farnsworth’s image dissector

🎥 RCA’s mass production push

📰 War coverage proving its power

🏠 The living room revolution

The Break in the Case

The fairground hums. The crowd gathers.

1939 — RCA unveils television at the World’s Fair.

A Franklin speech flickers across the screen, and the future becomes visible.

Then war arrives.

Television halts, but not for long. When peace returns, so does the broadcast boom.

By 1950, homes glow blue at night. Families huddle around the screen like a new hearth.

The radio that once spoke in whispers now looks like furniture from another age.

“The picture replaced the voice, but the connection remained the same.”

The Verdict

Television wasn’t born in a lab. It was smuggled out of workshops, powered by stubborn dreamers and opportunists.

Dismissed as novelty, feared as narcotic, it became civilization’s mirror—showing us who we were, and sometimes, who we wished we weren’t.

It didn’t kill radio. It expanded the frequency of imagination.

One more case closed.

Dismissed at first, vindicated together.

Epilogue Hook — The Next Frequency

As the screen fades to static, a cursor blinks on a phosphor-green monitor.

The detective leans back. “Another case just came in. Something called… The Net.”

Coming soon:

🗞️ Next Week on Resistance Files