The Hidden Cost of Star Hires (And the Filter That Stops It)

🔒 Leader's Dispatch: Volume 27 (Chaos Agents, Part 1 of 3 Part Series)

Previous:

Chaos Agents (Part 1 of 3): Seduction (The Invitation)

Your Star Hire Just Broke the Rules

One exception becomes precedent. Here’s the Invitation Filter that stops it early.

Teams don’t break because stars are intense. They break when leaders reward output with immunity. Here’s the three-gate system that keeps standards intact.

You hired the star. The team exhales.

Then you grant the first exception, and the rules stop being rules.

Procedural injustice predicts a 51% drop in commitment and a 34% rise in withdrawal behavior. The research is clear: when leaders treat standards as negotiable for high performers, the entire team notices. What feels like “being flexible” is actually a precedent engine that teaches everyone else which rules are real and which ones dissolve under pressure.

This piece gives you the Invitation Filter: a five-question diagnostic that catches exception creep at three gates, pre-offer, Day 30, and Day 90. Before it metastasizes into culture.

Script line (copy/paste):

“If this exception cannot be generalized to the entire team, it’s a risk, not a perk.”

Proof pin:

Procedural justice research shows strong correlations with commitment (ρ = -0.51), job satisfaction (ρ = -0.50), withdrawal behaviors (ρ = 0.34), and evaluation of authorities (ρ = 0.56). When people perceive the process as unfair, they check out. Even when they agree with the outcome.

Takeaway

Stars don’t break teams by being intense or demanding.

Teams break when leaders reward output with immunity from the systems everyone else follows.

It starts with results. The dependency builds through exceptions. And by the time you notice, the precedent is set and the rest of the team has gone quiet.

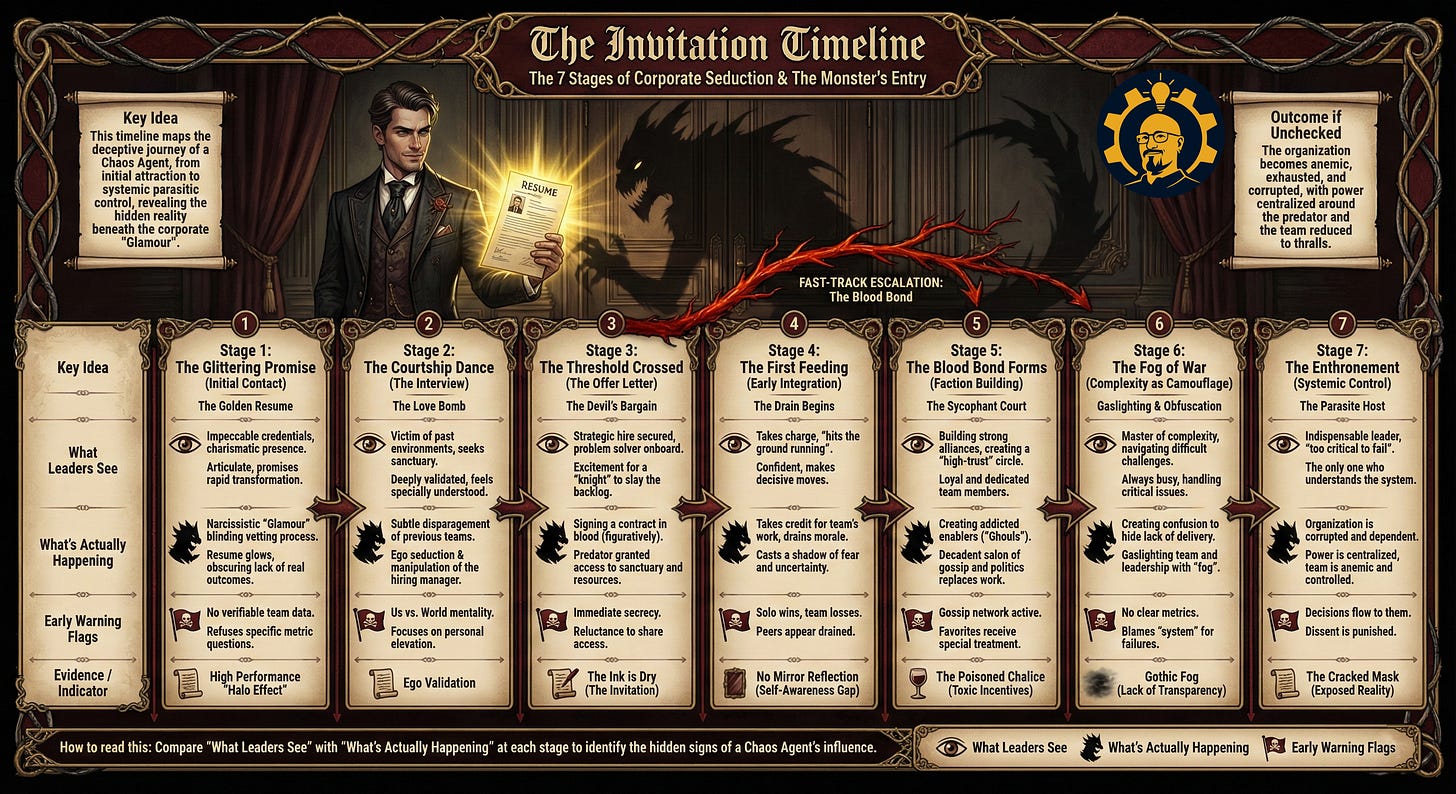

Exhibit 1: The Invitation Timeline (7 stages)

This timeline tracks two parallel stories that most leaders miss until it’s too late.

What leaders see: Speed. Confidence. Relief. The hire is closing deals, shipping code, or landing clients faster than anyone else. The output justifies the investment. The team seems fine. Everything looks good.

What’s actually happening: Precedent is being set. Dependency is building. Standards are drifting.

Example: Leader sees: “She closed the enterprise deal in 72 hours.” What’s actually happening: “She bypassed the legal review process and set a precedent that the next three sales hires will request within their first 60 days.”

The inflection point is Stage 3. The first time a leader says, “Normally we don’t do this, but…” that sentence is the invitation. It signals to the star that the rules are negotiable. It signals to the team that fairness is optional.

Most chaos doesn’t arrive as obvious villainy. It arrives as a solution to an urgent problem. The star becomes the exception because they’re solving problems faster than your process can keep up. That’s when leaders get seduced into flexibility. And flexibility, without guardrails, becomes the new operating system.

The Invitation Filter: What’s Inside It

The Invitation Filter is a five-question diagnostic you run before granting any exception to a new hire. It takes eight minutes. You use it at three moments: before extending the offer, at the 30-day gate, and at the 90-day gate.

Here are the five questions:

1. Can this exception be generalized to the entire team without breaking operations?

If you can’t extend this flexibility to everyone, you’re creating a two-tier system. Two-tier systems produce resentment faster than almost anything else in organizational life.

2. What precedent does this set, and who will request it next?

Exceptions don’t stay contained. If you let the star skip sprint planning, the next three engineers will ask for the same accommodation. If you say yes again, sprint planning is now optional. If you say no, you’ve just told them the rules depend on who’s asking.

3. What written documentation will this person produce in the next 30 days to offset this flexibility?

Exceptions come with a price. If you’re granting process flexibility, require knowledge transfer in return. Documentation. Recorded demos. Pair programming sessions. Runbooks. Make the trade explicit.

4. If this person left tomorrow, would this exception block the team’s ability to operate?

This is the bus factor question. If the answer is yes, you’re not granting an exception. You’re installing a single point of failure.

5. Am I granting this because of evidence, or because I’m relieved they’re here?

Desperation makes bad policy. If you’re saying yes because you’re grateful they signed, you’re negotiating from weakness. That relief will cost you later.

Decision rule: If you answer “no” to question 1, or “yes” to question 4 or 5, the answer is no. If you’re uncertain on questions 2 or 3, document the trade explicitly and set a 30-day review gate to assess whether the documentation happened.

A Real Tuesday Afternoon: How the Filter Works in Practice

Sarah was hiring a senior backend engineer. The candidate, Alex, had stellar references and a track record of shipping fast. During the final interview, Alex mentioned he preferred working async and rarely attended standups at his previous company.

The hiring manager’s instinct was to say yes. Alex was solving a critical gap. The team needed velocity. Standups could be flexible.

Then Sarah pulled up the Invitation Filter.

Question 1: Can we generalize this? If we make standups optional for Alex, can we make them optional for the other four backend engineers? The answer was no standups were how the team coordinated on blockers. Making them optional for one person would fracture communication.

Question 2: What precedent does this set? If Alex skips standups, the next senior hire will ask for the same thing. And if Sarah says no to them, she’s just told them the rules depend on seniority or negotiation leverage.

Question 5: Am I saying yes because of evidence, or relief? Sarah realized she was relieved to have found someone with Alex’s background. That relief was doing the thinking.

She made the offer. But she also said this: “Standups are how we coordinate. If you find they’re not valuable, let’s talk about changing them for everyone. But I can’t make them optional just for you. It would break trust with the team.”

Alex accepted. He attended standups. Three months later, he proposed a better async update system that the entire team adopted. The system worked because it applied to everyone.

If Sarah had granted the exception, Alex would have learned the rules were negotiable. The team would have learned fairness was optional. And six months later, Sarah would have been managing resentment instead of coordination.

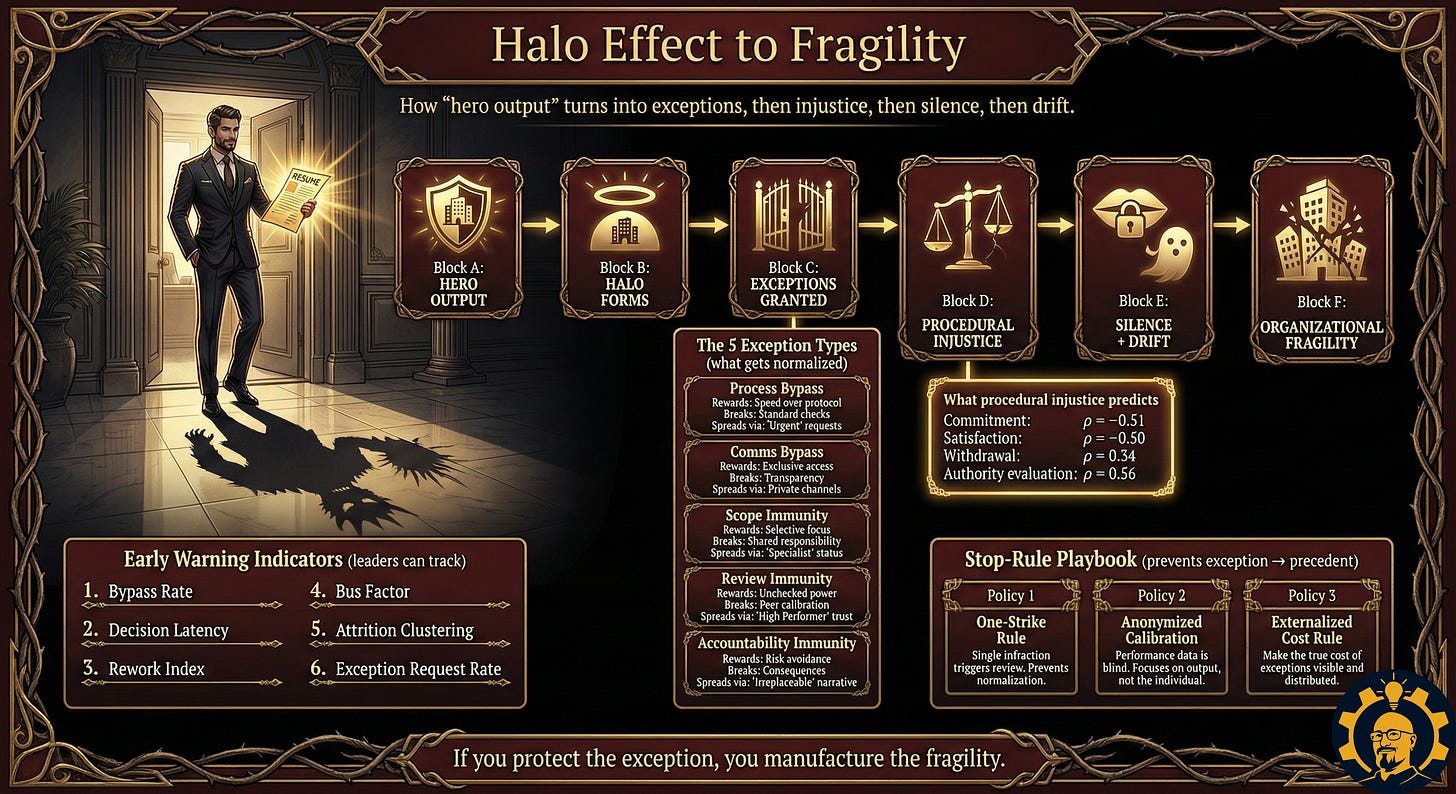

Exhibit 2: Halo Effect to Fragility

Here’s the causal chain that most leaders don’t see until it’s too late:

Hero output creates a halo.

The halo produces exceptions.

Exceptions produce procedural injustice.

Procedural injustice produces silence and drift.

Silence creates fragility.

Let’s define silence operationally, because it’s the part leaders miss. Silence looks like:

Team members stop flagging issues in standups

1:1s get shorter and more surface-level

Slack participation drops in shared channels

The ratio of team-initiated feedback to leader-initiated check-ins falls below 2:1

People start saying “it’s fine” when you ask how things are going

Silence is not peace. Silence is withdrawal. And withdrawal predicts turnover.

The leadership trap lives here: the team learns the rules are real and enforceable, until a charismatic producer shows up. Then the rules become suggestions. The team doesn’t quit immediately. They go quiet first. And by the time you notice the attrition, the best people have already started interviewing elsewhere.

Track that ratio. If team-initiated feedback drops below 2:1 compared to leader-initiated check-ins, silence is setting in. That’s your early warning system.

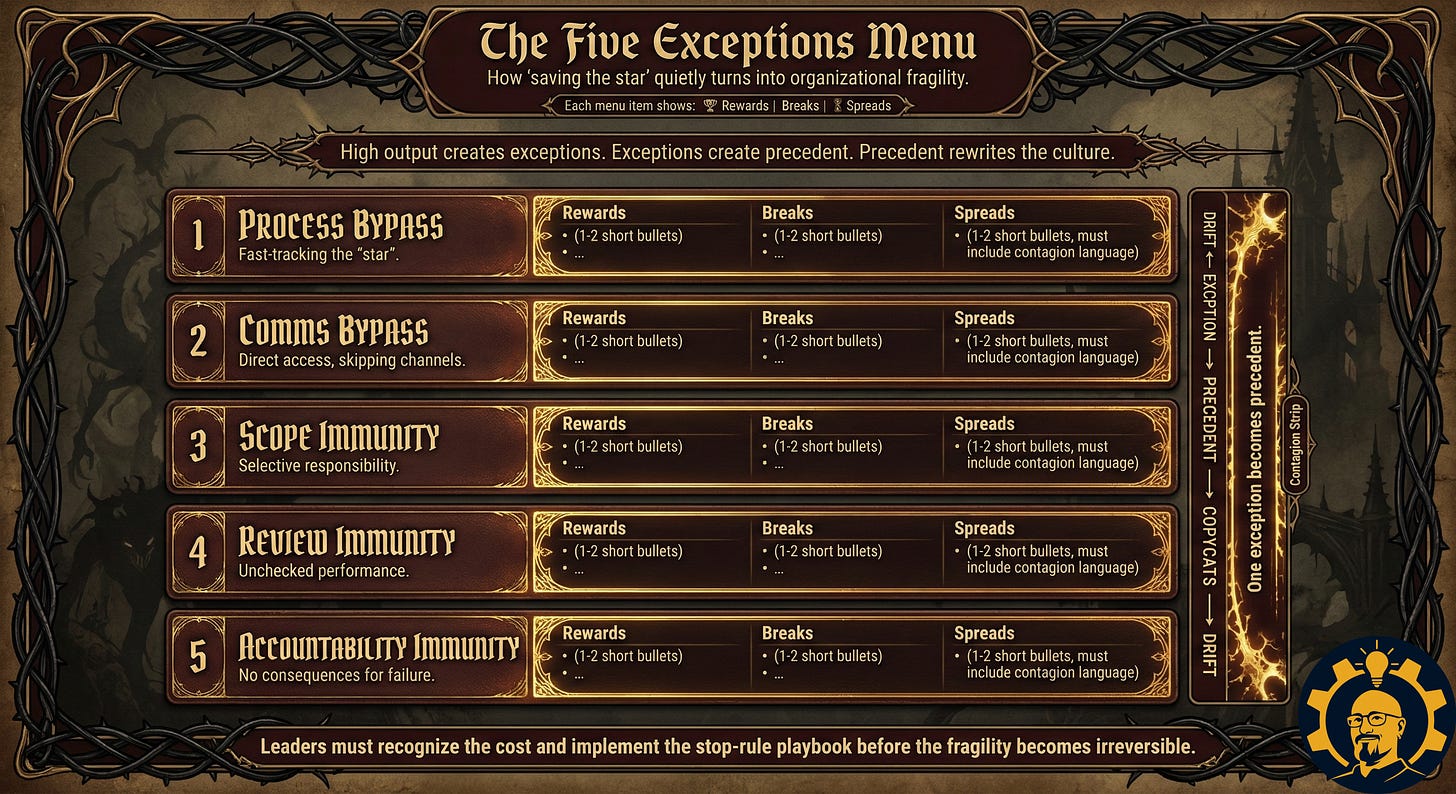

Exhibit 3: The Five Exceptions Menu

Five exception types leaders accidentally serve to star hires:

1. Process bypass

Skipping sprint planning, code review, security sign-off, or legal approval.

Example: “I’ll just ship this hotfix directly to prod, we can document it later.”

Response script: “I hear the urgency. If this process isn’t worth doing, let’s kill it for everyone. If it is, it applies to you too. Which one?”

2. Comms bypass

DMing the CEO instead of escalating through their manager. Skipping team channels for private backchannels.

Example: “I pinged the VP directly since you were in meetings.”

Response script: “If I’m a bottleneck, let’s fix that. But skipping the chain creates confusion for everyone else. Use the standard escalation path, and I’ll make sure it’s fast.”

3. Scope immunity

Changing project scope mid-sprint without negotiation. Committing the team to deadlines without consulting them.

Example: “I told the client we’d have this done by Friday.”

Response script: “I appreciate the hustle. And I can’t have you committing the team without checking capacity first. Let’s align on how we make scope decisions.”

4. Review immunity

Declining code review, skipping design critiques, or treating feedback as optional.

Example: “I’ve been doing this for ten years, I don’t really need review on this.”

Response script: “Review isn’t about trust. It’s about knowledge transfer and catching blind spots. Everyone gets reviewed, including me.”

5. Accountability immunity

Missing deadlines without explanation. Avoiding retrospectives. Treating postmortems as optional.

Example: “I don’t think I need to be in the retro, I wasn’t involved in the incident.”

Response script: “Retros are how we learn as a team. Your perspective matters even if you weren’t directly involved. If retros aren’t useful, let’s fix them. But skipping them isn’t an option.”

One exception becomes precedent. Precedent teaches everyone what’s safe to copy. The star learns the house rules are negotiable. The team learns fairness is optional. Silence starts paying interest.

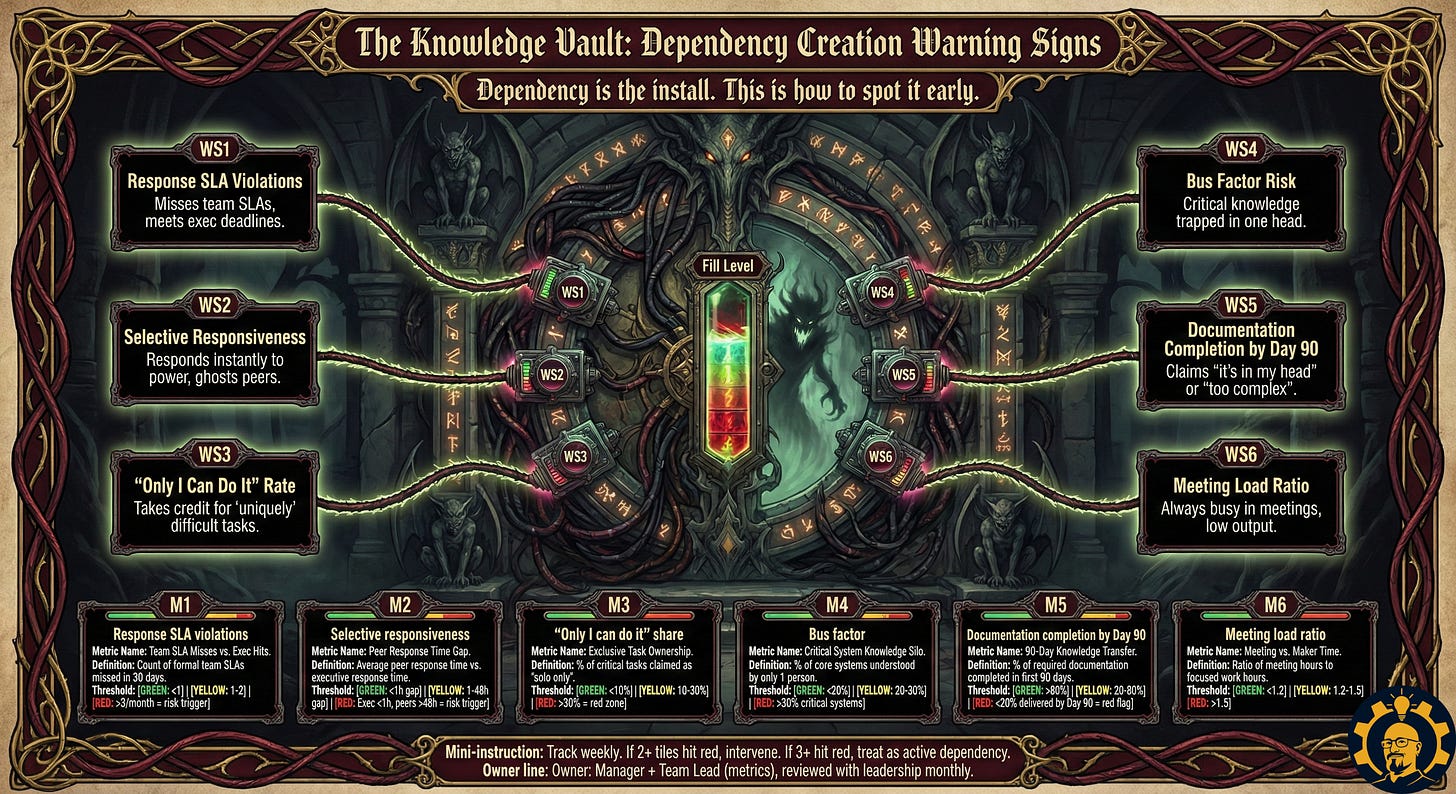

Exhibit 4: The Knowledge Vault (Dependency Creation Warning Signs)

Dependency is the real risk. A team can survive a difficult personality. A team cannot survive concentrated knowledge paired with selective access.

Here’s how to measure it. Use this scorecard weekly for the first 90 days:

Score 1 point for each signal:

Undocumented processes that only this person understands

Meetings this person runs alone with no backup

Requests that only they can fulfill (no redundancy)

Projects that pause or stall when they’re out of office

Team members who defer to them without checking their own judgment

Knowledge that lives in their head, not in wiki/docs/runbooks

Critical vendor or client relationships with no shared access

Scoring:

0–2 points: Green. Normal onboarding.

3–4 points: Yellow. Trigger a 30-day knowledge transfer sprint.

5+ points: Red. Dependency is building. Start containment immediately.

What does containment look like? Forced pair programming. Required documentation PRs. Shadow sessions where team members observe and document. Weekly knowledge-sharing standups. The goal is to distribute what’s concentrated before it becomes a single point of failure.

Track these metrics explicitly:

Bus factor: How many people need to be hit by a bus before this project stops?

Documentation coverage: What percentage of this person’s work has written artifacts?

Cross-training sessions: How many hours per week is this person spending teaching others?

If the bus factor is 1 and the documentation coverage is below 40% after 60 days, you’ve already installed dependency. Fix it before it becomes leverage.