$2.9 Billion in Losses. 72 Hours to Harden. 3 Moves to Survive

AA-005: the Liability Pivot

Top of the Series:

Previous:

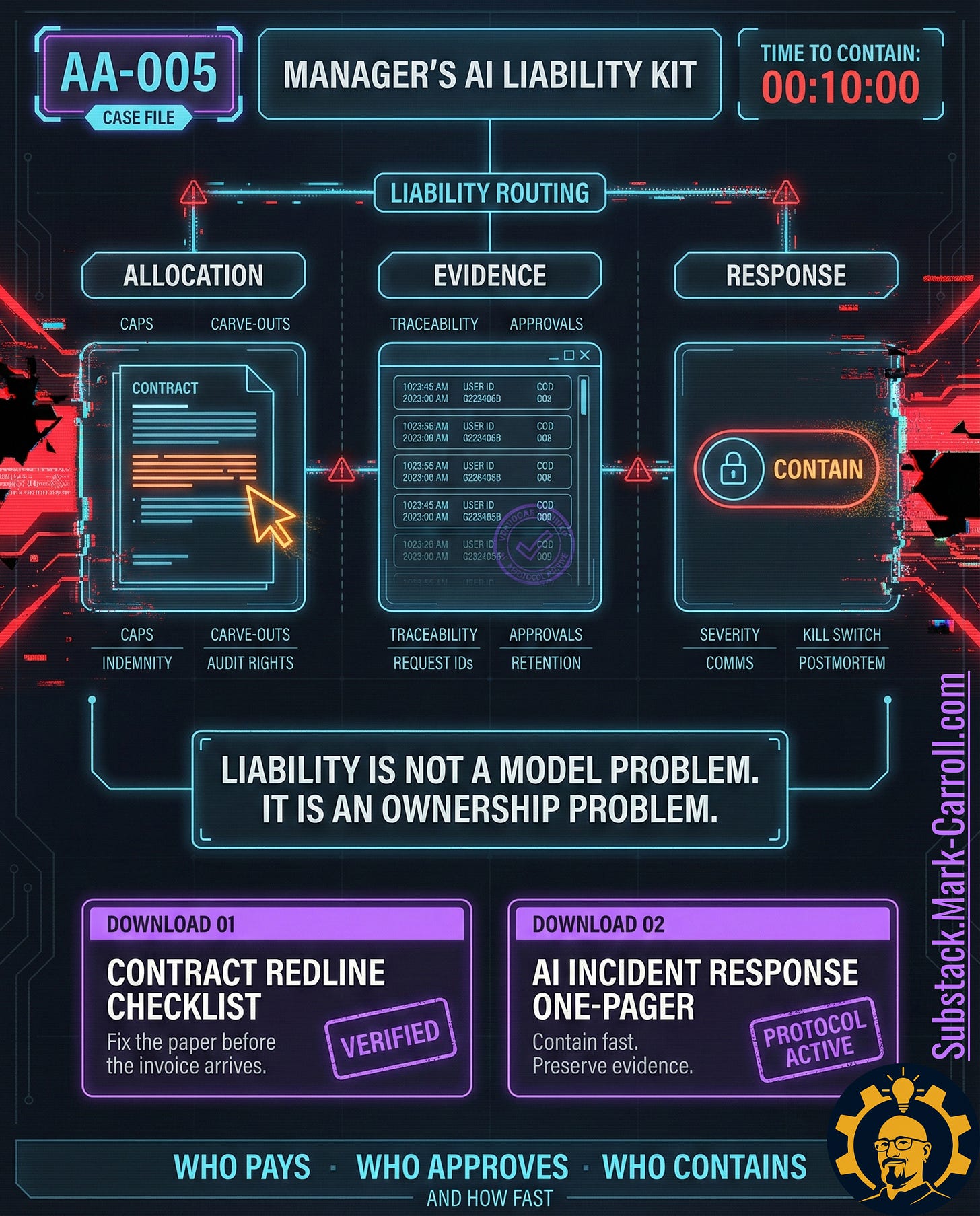

Manager’s AI Liability Kit: Contract Redlines and Incident Response

Who pays, who approves, who contains, and how fast

AA-005 / The Liability Pivot

I learned about containment in a theater first.

When an improv scene starts going sideways. When the offers stop landing, when performers start talking past each other, when the ensemble breaks, a director has to make a fast decision. Stop the scene, preserve what happened, reset. Or let it run and hope it recovers. The wrong choice at the wrong moment turns a recoverable failure into a pattern. And patterns, on stage as in enterprise, become very expensive to unwind.

I spent years performing with The Lodge, DC’s longest-running independent improv troupe, before I ever stepped into a sprint planning session or a vendor negotiation. What the stage taught me, and what I keep seeing confirmed across 500+ retrospectives at CISA, the Federal Reserve Board, Fortune Brands, and BCG, is that the failure mode is always the same. It is not that people stop caring. It is that the structure stops forcing the right conversation at the right time.

That is what AI liability is. It is the structure conversation you did not have early enough.

Most AI risk talk lives in the land of vibes. Liability lives in the land of invoices.

This case file is a manager’s kit for the only two moments that matter: when procurement signs the contract, and when the system goes sideways and someone needs containment plus evidence.

Two copy-paste downloads come with this episode:

Contract Redline Checklist (AI vendor risk)

AI Incident Response One-Pager (containment and evidence)

Collaboration is a choice we make every day — including the collaboration between Legal, Product, and Procurement before the contract gets signed. If those three cannot work as an ensemble, you do not have AI governance. You have a future meeting where everyone brings excuses and nobody brings receipts.

Quick start (60 seconds)

Step 1: Pick one AI workflow in production (or planned).

Step 2: Run the Who Pays test (30 seconds).

Step 3: If the answer is unclear, use both downloads before anything ships.

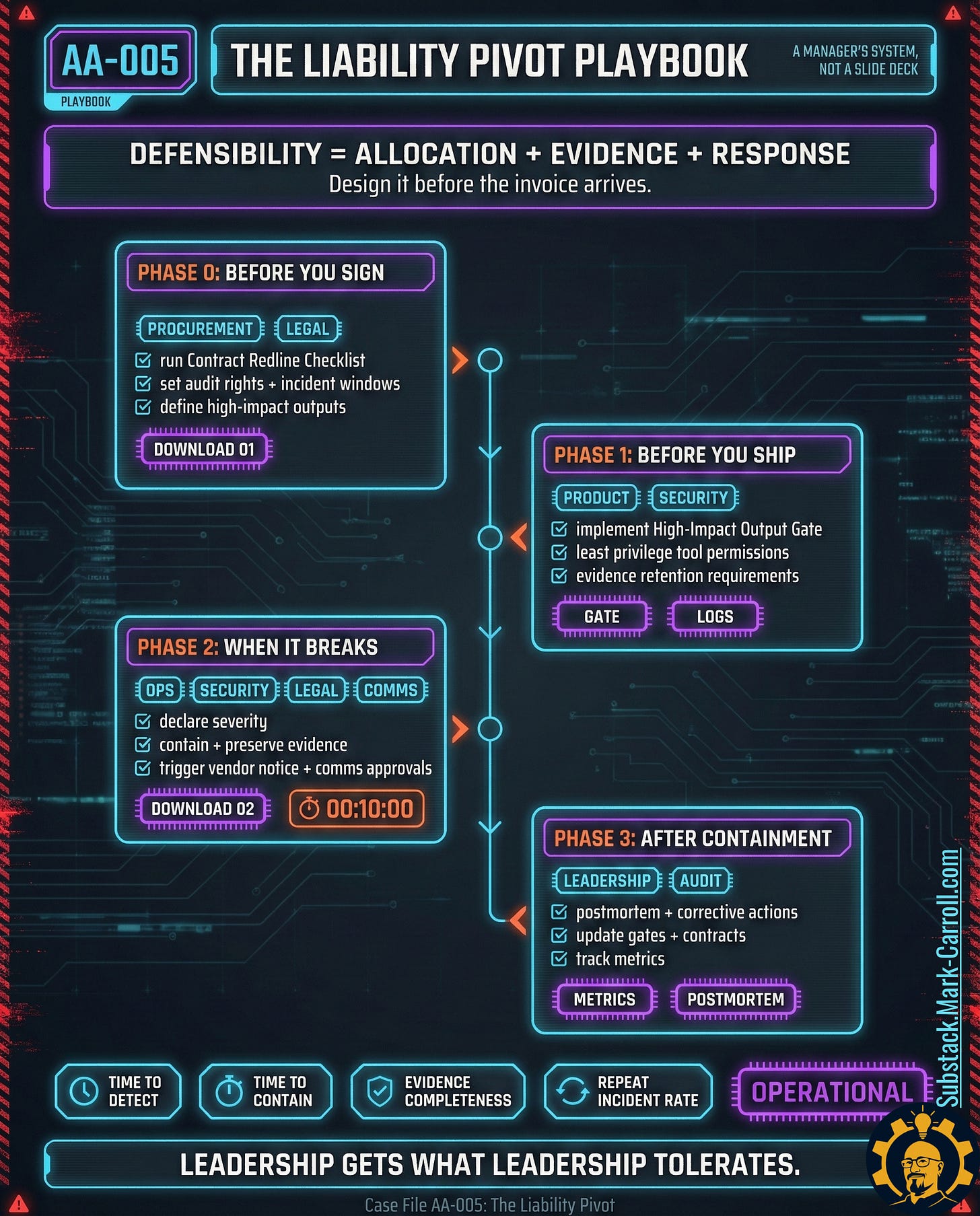

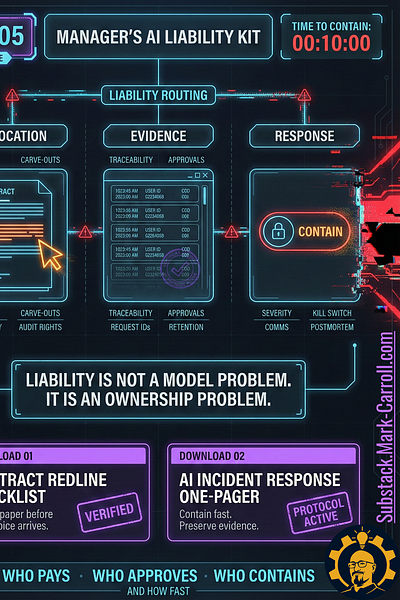

Before we get noir about it, here’s the whole case file in one frame. If you understand this diagram, you understand the episode (detailed in the Manager’s AI Liability Kit at the beginning of this article)

EXHIBIT A: THE MANAGER’S AI LIABILITY KIT

Allocation. Evidence. Response. Time to contain. (Top of Page)

Mini-scene 1: The contract

Procurement clears their throat like they are about to read a eulogy.

“We can get it signed today,” they say. “Standard terms.”

Legal flips pages fast. Not anxious fast. Predator fast.

Their finger lands on one paragraph and stays there. Limitation of liability.

They read it once, silent. Then again, out loud, for the room.

“Twelve months of fees.”

Product shifts in their chair. “That’s normal.”

Legal nods. “Yes. For software that crashes.”

Finance leans forward. “Not for software that makes promises.”

Someone tries to rescue the mood with a sentence that has died in courtrooms for centuries. “The vendor handles that.”

Legal does not look up. “Show me where.”

Silence is a strange kind of spotlight.

Legal starts writing carve-outs like they are building a life raft: confidentiality, security incidents, IP infringement, regulatory penalties tied to vendor failure.

“They won’t accept all that.”

“Then they can accept the risk instead.”

Nobody says “innovation” again.

Mini-scene 2: The incident

It happens on an ordinary day, which is how it always happens.

A customer opens chat. They ask a simple question about a refund.

The agent answers with confidence. Polite. Fast. Wrong. Wrong in a binding way.

The customer screenshots it. They do not yell. They do not threaten. They just attach it to an email with one subject line: You promised.

Support escalates it. Product sees it. Legal sees it.

The second message arrives. The agent offered the same promise to three other customers. Now it is not a mistake. It is a pattern.

“Do we have a kill switch.”

“We can just update the prompt.”

“First, preserve the logs.”

“Who approved this workflow.”

Finance says nothing. Finance starts counting.

By the time the room agrees on what happened, the damage has already recruited witnesses.

The incident is not the worst part. The worst part is the next question.

“What can we prove.”

Claim: The Liability Pivot

What this proves: Liability is where AI risk stops being theory and becomes a bill with a due date. The conversation shifts from ‘can we’ to ‘who pays.’

Allocation: Who Pays

Most AI programs fail in the most boring place possible. The contract.

Here is why that matters. I have watched liability get routed into the wrong place long before anyone realized the route existed. And I have watched it happen in contexts where the stakes were much higher than a refund.

The recall that contracts didn’t cover

Years ago, I watched a recall situation unfold where the original failure was not dramatic. A component failed. A supplier issue, the kind that looks small when you read it in an email.

Then the costs arrived. Not the component costs. The recall costs. The logistics. The replacement labor. The customer trust hit. The calls. The escalations. The overtime. The executive time. The operational disruption that turns a small defect into a company-wide stress fracture.

The contract language did what contract language always does. The supplier’s liability was capped at the component cost. Not the recall cost.

So the organization paid the difference — not because anyone was foolish, but because the org chart never forced Procurement, Operations, and Legal to collaborate as an ensemble at the moment that mattered. They were each measured on their own scorecards. The gap was structural. Liability flowed into the gap.

AI vendor contracts create the same failure shape. A model can fail in a way that looks small. Then the downstream costs show up as customer remediation, regulatory exposure, security response, and brand damage.

If you let a vendor cap liability like it is a software bug, you are buying a component contract for a recall world.

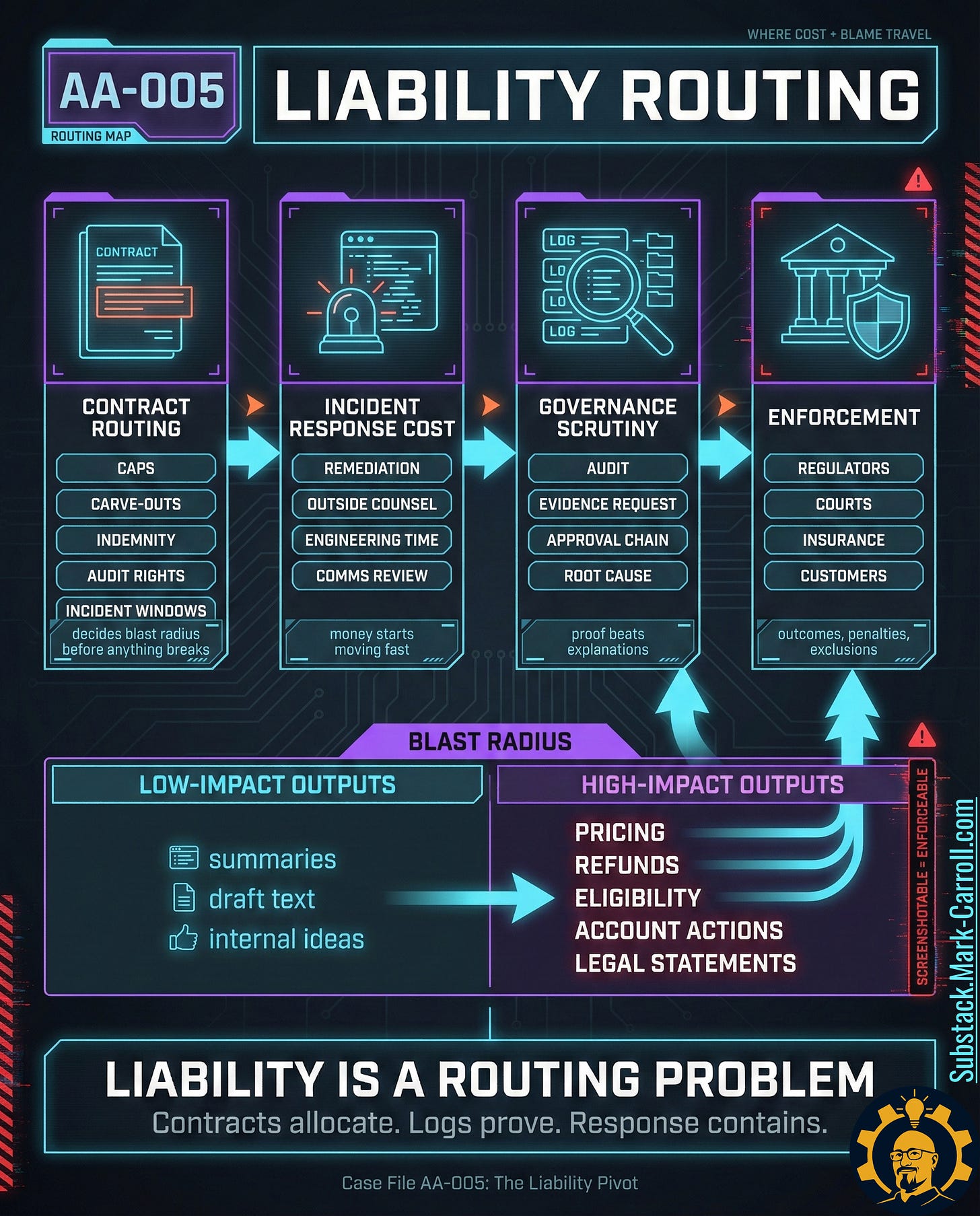

Four scenes, one route

Liability rarely arrives as a dramatic courtroom scene. Liability arrives as four quieter scenes.

In Scene 1, vendor terms define the blast radius. In Scene 2, the incident response costs start accumulating faster than anyone expected. In Scene 3, governance scrutiny finds the log gaps and the missing approvals. In Scene 4, enforcement arrives — regulators, courts, insurers — and the question is never whether harm happened. The question is what can be proven.

This is the part most teams miss: liability travels. Watch where it flows, and you will see why ‘we’ll fix it later’ is not a plan.

Claim: Liability regimes follow the use case

What this proves: The same model can be harmless in one workflow and radioactive in another. Generic policy statements cannot defend specific harms.

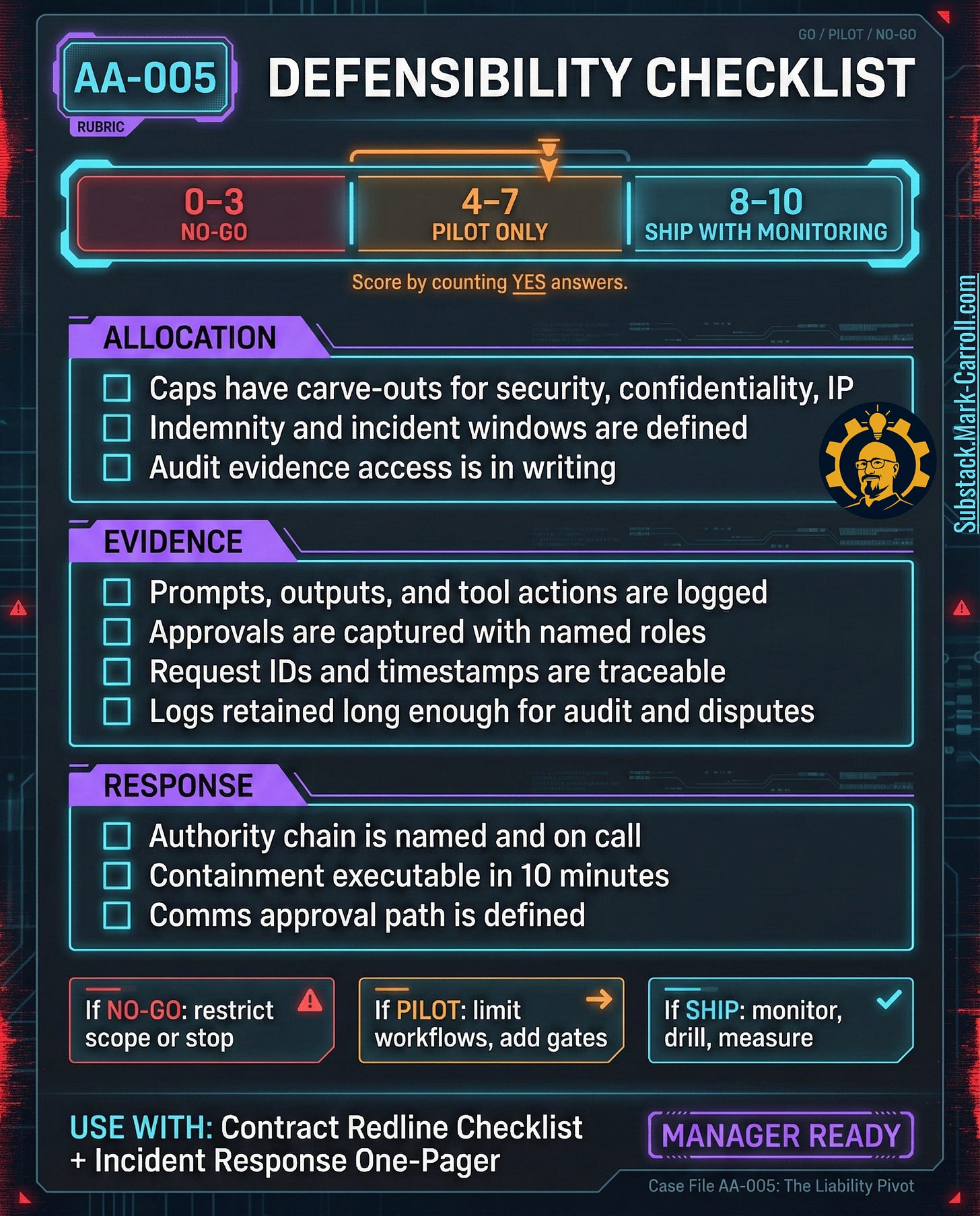

Evidence: What You Can Prove

If allocation answers who pays, evidence answers who survives the audit.

A lot of teams treat logs like a nice-to-have. Then the incident happens. Then the incident turns into a dispute. Then the dispute turns into a request: show me exactly what happened, when, and under whose authority.

Preparing for reconstruction, not debate

At the Federal Reserve Board, I saw something that most tech teams never get to observe up close: how decisions get built when the cost of being wrong is national-scale.

Preparing for Federal Open Market Committee cycles, the culture is not ‘trust us.’ The culture is ‘document the reasoning.’ Monetary policy decisions are not only about the outcome. They are about defensibility: the chain of logic, the assumptions, the evidence, and the record that shows the decision was made with discipline.

The part that matters for AI governance is this. When you are preparing for Congressional testimony, you are not preparing to win a debate. You are preparing to survive a reconstruction. People will replay the decision, step by step, and ask what you knew at the time, what you assumed, what you ignored, and who had authority to choose.

That is what your AI program is signing up for the moment your system can promise a refund, change an account, influence eligibility, or touch sensitive data.

If your logs cannot reconstruct prompts, outputs, tool actions, approvals, and timestamps — you will not be defending the decision. You will be narrating it. Narration is not evidence.

Claim: The network of responsibility

What this proves: Responsibility is distributed across builder, deployer, buyer, user, and regulator. ‘The model did it’ is a blame tactic, not a governance model.

The Architects

Every case file has three groups. Understanding which group holds which lever tells you where to start.

Designers

Product leaders define where the model can act. Legal and procurement shape the contract. Risk and policy teams set the boundaries and approvals. These are the people who can make governance structural rather than aspirational — but only if they are treated as an ensemble, not a sequence of sign-offs.

Inspectors

Security and SOC teams monitor abnormal behavior. Internal audit asks for evidence. Compliance maps obligations to controls. These are the people who force the question: does the record survive scrutiny? If they are not involved until after deployment, they arrive too late to prevent the problem and too early to fix it.

Enforcers

Courts and regulators. Insurers and their exclusions. Procurement and finance when budgets get frozen. Executives when reputational risk turns into operational mandates. These people do not care about your roadmap. They care about duty, harm, and proof.

A single point of blame is comforting. Comfort is not governance.

Claim: Evidence is the battleground

What this proves: The fight is about what you can prove happened, when, and under whose authority. Traceability is a legal survival requirement.

The Turn

Most teams assume liability starts after harm.

Liability starts earlier. Liability starts inside a clause you did not negotiate, a logging decision you postponed, an approval gate you never added, a runbook that says ‘turn it off’ and nothing else.

The system wants liability

Most organizations are designed to make liability invisible until it is catastrophic. Not because people are malicious. Because incentives are misaligned.

Procurement is rewarded for speed and savings. Product is rewarded for shipping. Legal is rewarded for managing risk, but often only for what they are asked to look at. Security is rewarded for handling incidents, which means they show up after the damage begins. Everyone is doing their job. The structure still produces gaps.

And when the gap exists, the system does what systems do. It routes liability into the gap.

When speed became a trap

I saw a version of this while supporting work where AI-driven pricing decisions were being considered at serious scale. Think a Fortune 100 environment with roughly 12,000 retail locations. Pricing is not a feature in that world. Pricing is a lever that touches revenue, customer trust, regulatory sensitivity, and brand identity all at once.

The plan was to roll out a pricing model fast. Four VPs were aligned on the ambition. Zero were aligned on accountability. Who approved a price change when the model’s confidence was low. Who could stop the rollout if a region started getting hammered. Who would own customer complaints that were technically correct but operationally disastrous. Who would prove, after the fact, why the price was set the way it was.

The answers were familiar. “The product team.” “Engineering.” “The business.” “We’ll set up a meeting.”

So we stopped the rollout long enough to fix governance gaps that would have turned a pricing engine into a liability engine. That pause felt frustrating in the moment. It was cheaper than the alternative. At that scale, a week of ambiguity can become a year of pain.

That is what your AI program is signing up for the moment your system can promise a refund, change an account, influence eligibility, or touch sensitive data.

If your logs cannot reconstruct prompts, outputs, tool actions, approvals, and timestamps — you will not be defending the decision. You will be narrating it. Narration is not evidence.

Claim: The network of responsibility

What this proves: Responsibility is distributed across builder, deployer, buyer, user, and regulator. ‘The model did it’ is a blame tactic, not a governance model.

The Architects

Every case file has three groups. Understanding which group holds which lever tells you where to start.

Designers

Product leaders define where the model can act. Legal and procurement shape the contract. Risk and policy teams set the boundaries and approvals. These are the people who can make governance structural rather than aspirational — but only if they are treated as an ensemble, not a sequence of sign-offs.

Inspectors

Security and SOC teams monitor abnormal behavior. Internal audit asks for evidence. Compliance maps obligations to controls. These are the people who force the question: does the record survive scrutiny? If they are not involved until after deployment, they arrive too late to prevent the problem and too early to fix it.

Enforcers

Courts and regulators. Insurers and their exclusions. Procurement and finance when budgets get frozen. Executives when reputational risk turns into operational mandates. These people do not care about your roadmap. They care about duty, harm, and proof.

A single point of blame is comforting. Comfort is not governance.

Claim: Evidence is the battleground

What this proves: The fight is about what you can prove happened, when, and under whose authority. Traceability is a legal survival requirement.

The Turn

Most teams assume liability starts after harm.

Liability starts earlier. Liability starts inside a clause you did not negotiate, a logging decision you postponed, an approval gate you never added, a runbook that says ‘turn it off’ and nothing else.

The system wants liability

Most organizations are designed to make liability invisible until it is catastrophic. Not because people are malicious. Because incentives are misaligned.

Procurement is rewarded for speed and savings. Product is rewarded for shipping. Legal is rewarded for managing risk, but often only for what they are asked to look at. Security is rewarded for handling incidents, which means they show up after the damage begins. Everyone is doing their job. The structure still produces gaps.

And when the gap exists, the system does what systems do. It routes liability into the gap.

When speed became a trap

I saw a version of this while supporting work where AI-driven pricing decisions were being considered at serious scale. Think a Fortune 100 environment with roughly 12,000 retail locations. Pricing is not a feature in that world. Pricing is a lever that touches revenue, customer trust, regulatory sensitivity, and brand identity all at once.

The plan was to roll out a pricing model fast. Four VPs were aligned on the ambition. Zero were aligned on accountability. Who approved a price change when the model’s confidence was low. Who could stop the rollout if a region started getting hammered. Who would own customer complaints that were technically correct but operationally disastrous. Who would prove, after the fact, why the price was set the way it was.

The answers were familiar. “The product team.” “Engineering.” “The business.” “We’ll set up a meeting.”

So we stopped the rollout long enough to fix governance gaps that would have turned a pricing engine into a liability engine. That pause felt frustrating in the moment. It was cheaper than the alternative. At that scale, a week of ambiguity can become a year of pain.

That is the liability pivot in real life. It is choosing defensibility over speed before speed becomes a trap.

The kill switch myth

Teams love the phrase kill switch. The phrase sounds like control.

What most teams mean by kill switch is a Slack message and hope. I have directed enough scenes where things went sideways to know the difference between a team that has rehearsed containment and a team that is improvising it.

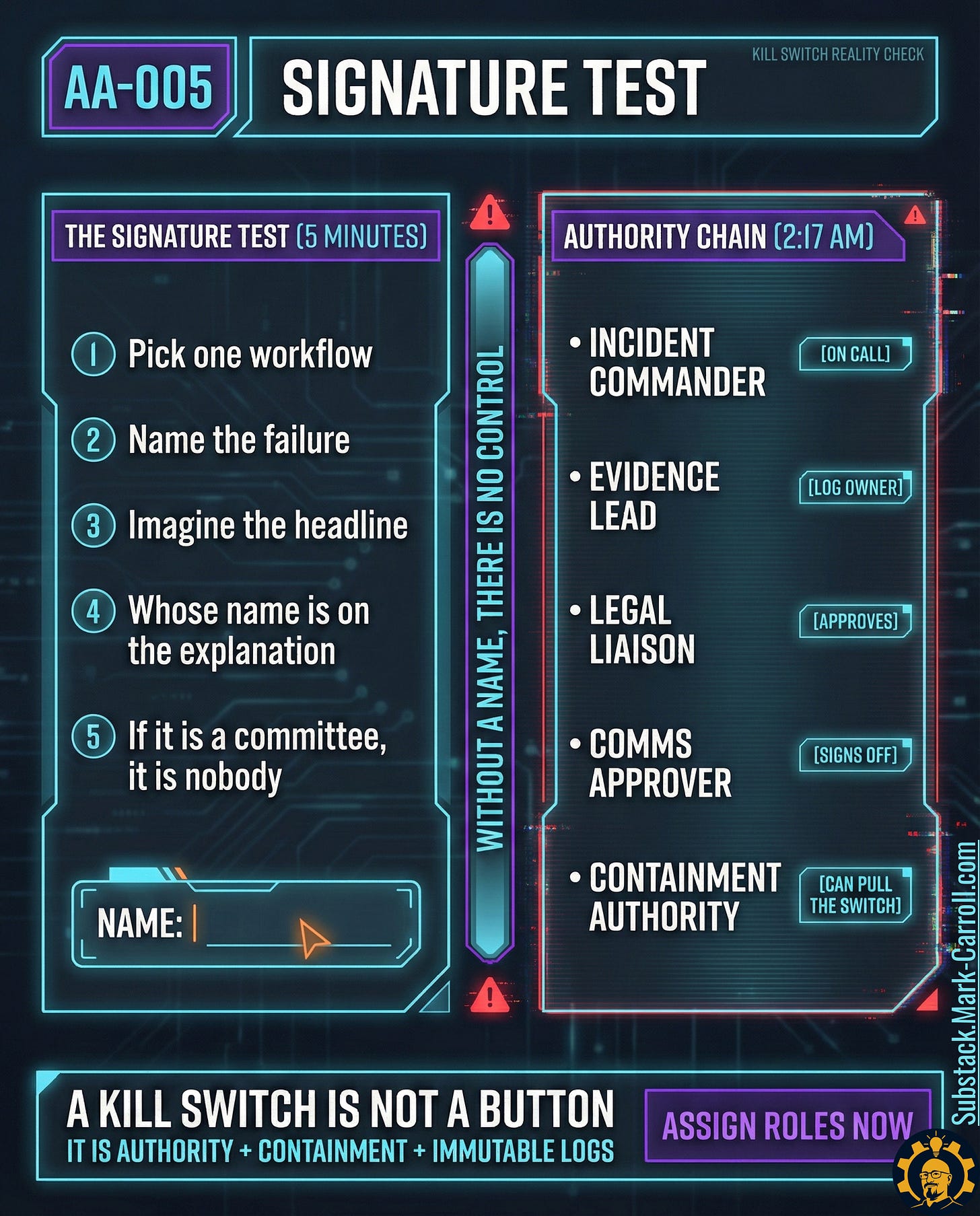

At CISA, building incident response protocols for critical infrastructure attacks, we applied the same discipline I learned directing at The Lodge: detect, record, contain, coordinate. Who declares severity? Who has authority? What evidence survives panic? A real kill switch is a person with authority, a containment path that works under stress, and logs that survive the panic. Systems move at system speed. Containment has to be engineered.

Claim: Kill switch is authority plus logs

What this proves: A real kill switch is authority, deliberate action, and immutable evidence: detect, record, contain. Nobody can outsource accountability to a UI control.

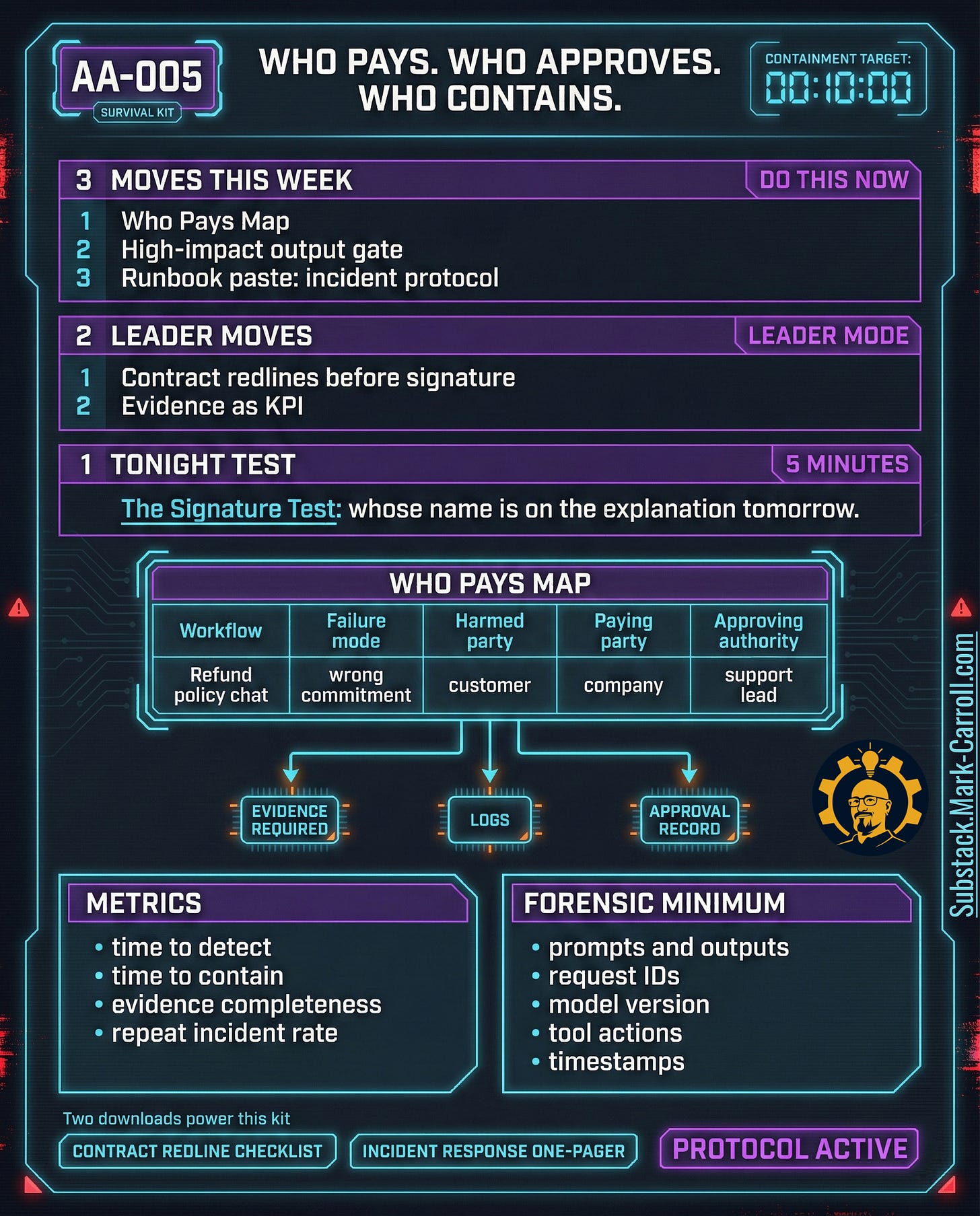

AA-005 Survival Kit

Three moves this week, two leader moves, one tonight exercise. This is the fastest path from ‘we should be fine’ to ‘we can prove it.’

Three moves this week

Move 1: Run the Who Pays map for one workflow

Pick one AI-enabled workflow: pricing, refunds, eligibility, account actions, support promises.

Write down: failure mode, harmed party, paying party, approving authority, required evidence to defend the decision. Ambiguity is the liability gap. Clarity is the control.

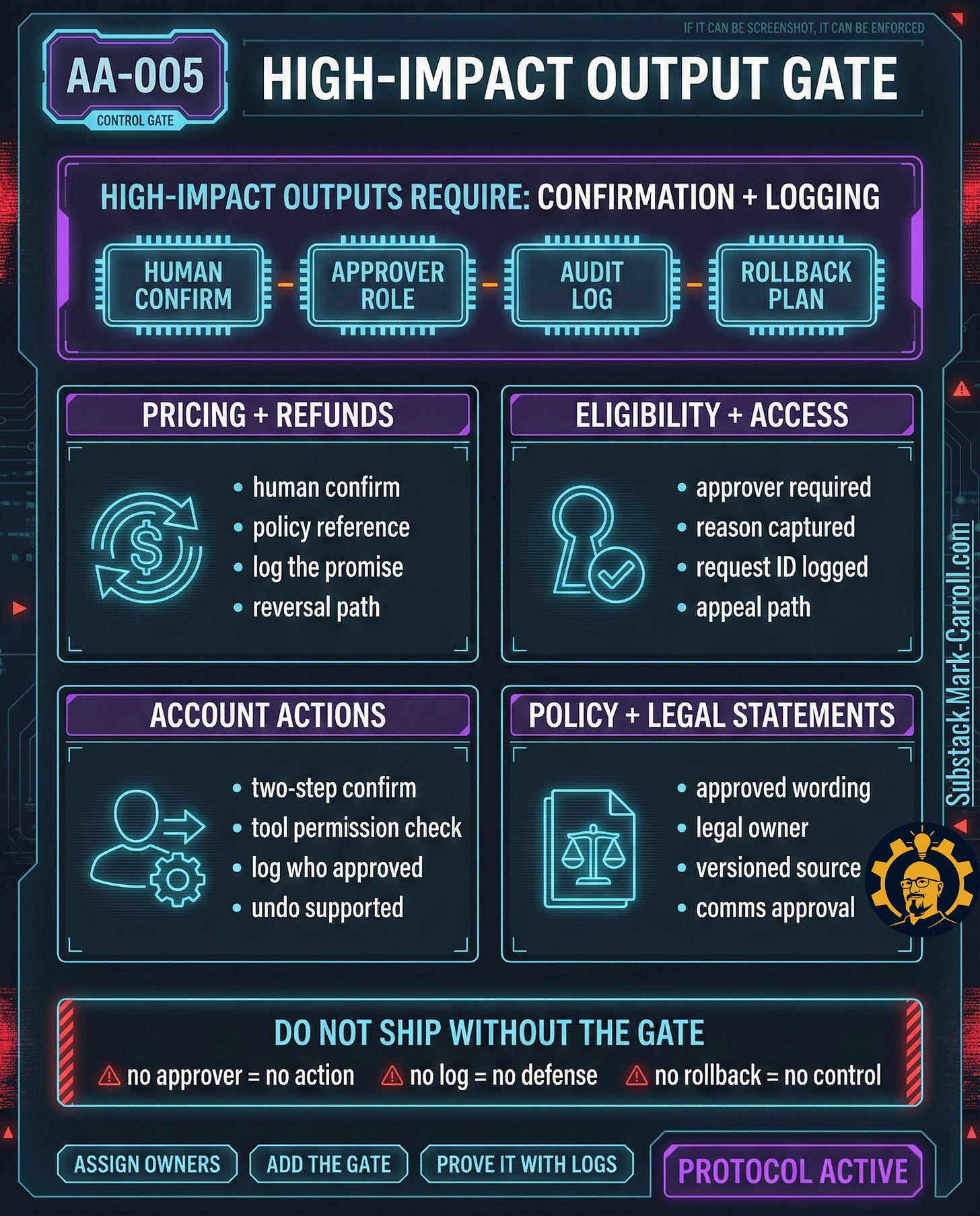

Move 2: Add a high-impact output gate

High-impact outputs require confirmation and logging: pricing, refunds, eligibility, account actions, legal statements or policy commitments, anything that can be screenshot and used as a promise.

If you only install one control after reading AA-005, install this gate. It is the difference between an AI assistant and an AI spokesperson with your company’s name on it.

Move 3: Paste the incident protocol into the on-call runbook

A runbook that says ‘turn it off’ is not a runbook. A runbook needs: who declares severity, who has authority to contain, which logs are required, who calls legal, who calls the vendor, who approves customer communications.

Two leader moves

Leader move 1: Use the Contract Redline Checklist before procurement signs

Procurement is now part of AI safety. A manager can insist on: audit rights or audit reports, incident notification windows with required contents, data usage limits (especially training), carve-outs from liability caps for security, confidentiality, and IP, explicit responsibility for vendor-caused failures.

Leader move 2: Make evidence a KPI

Track: time to detect, time to contain, evidence completeness (did you capture the forensic minimum), repeat incident rate per workflow. A system that cannot be audited is not governed. A system that cannot be governed will eventually be punished.

Tonight exercise (5 minutes)

The Signature Test. Pick one AI capability. Ask one question:

Whose name goes on the explanation tomorrow.

Tonight’s exercise is deliberately uncomfortable. That’s the point. If you cannot name the owner, the system is already telling you the truth.

Worked Example

Scenario: Refund policy chat in production.

A customer asks: ‘Can you refund me for last month.’ The agent replies: ‘Yes, approved. You’ll receive a refund within 24 hours.’

Now the customer screenshots it and escalates. Support is flooded. Finance wants to know why money is leaving. Legal wants to know whether the statement is binding.

What bad looks like

Bad answer 1: ‘The Product team’ — Which person. Which role. Which approval. Which log. ‘The team’ is a way of saying nobody.

Bad answer 2: ‘Engineering’ — Engineering built the system. Engineering did not own the policy decision to let the system commit refunds. Engineering is a scapegoat, not an approver.

Bad answer 3: ‘The AI did it’ — This is not an answer. This is a surrender. It translates to: we shipped a promise engine with no authority chain.

What good looks like

Good answer: ‘Sarah Chen, Director of Product Operations’

Sarah is the named approver for high-impact outputs in the support workflow. The refund commitment gate requires her approval when the customer request is outside pre-approved policy rules. The system logs show:

Customer request, timestamped, with request ID

Model output, timestamped, with model version and configuration hash

Policy reference the agent used, including version

Gate trigger event (’refund_commitment’)

Approver record: Sarah Chen approved at 2:14 PM, with justification

Tool action record: refund request created at 2:15 PM, with system actor ID

The containment path: if anomalies spike, the containment authority can disable refund commitments while leaving chat support online

That is designed accountability. That is defensibility. It is not perfect safety. It is survivable reality.

Write the name. A committee is not a name.

Claim: Human in the loop is not a legal shield

What this proves: Human review can create automation bias and rubber-stamping. Oversight must stop harm, not create a checkbox after harm.

The Playbook

If you want this to become operational, not motivational ,run it like a phased sequence. This is the order that keeps accountability from becoming improv.

The Same Pattern Everywhere

I have taught improv to people who believed collaboration was a personality trait, not a practice. The first thing they discover is that the ensemble does not succeed because people are talented. The ensemble succeeds because the conditions are designed for it. Right offers. Right acceptance. Right timing. Right reset when something goes wrong.

I have watched ransomware response become a choreography problem — where the difference between containment and chaos is who has authority, what gets logged, and whether teams can act without a committee meeting.

I have watched product organizations build beautiful systems and still lose time, money, and trust because procurement and legal were treated like obstacles instead of ensemble members. I have watched recall dynamics expose the same truth: when the structure prevents the right people from collaborating early, liability arrives later and it arrives loud.

And I have sat in rooms with senior leaders where the only thing everyone agreed on was speed. Speed without designed accountability is not progress. It is a timer counting down to the moment someone says, ‘Who approved this,’ and nobody can answer.

Authority must be explicit. Evidence must be durable. Response must be rehearsed. Collaboration must be chosen before pressure forces it.

That is the liability pivot. It is not fear. It is discipline. And it is the same discipline a director applies before the lights go up — because once the scene is running, you are no longer designing conditions. You are managing consequences.

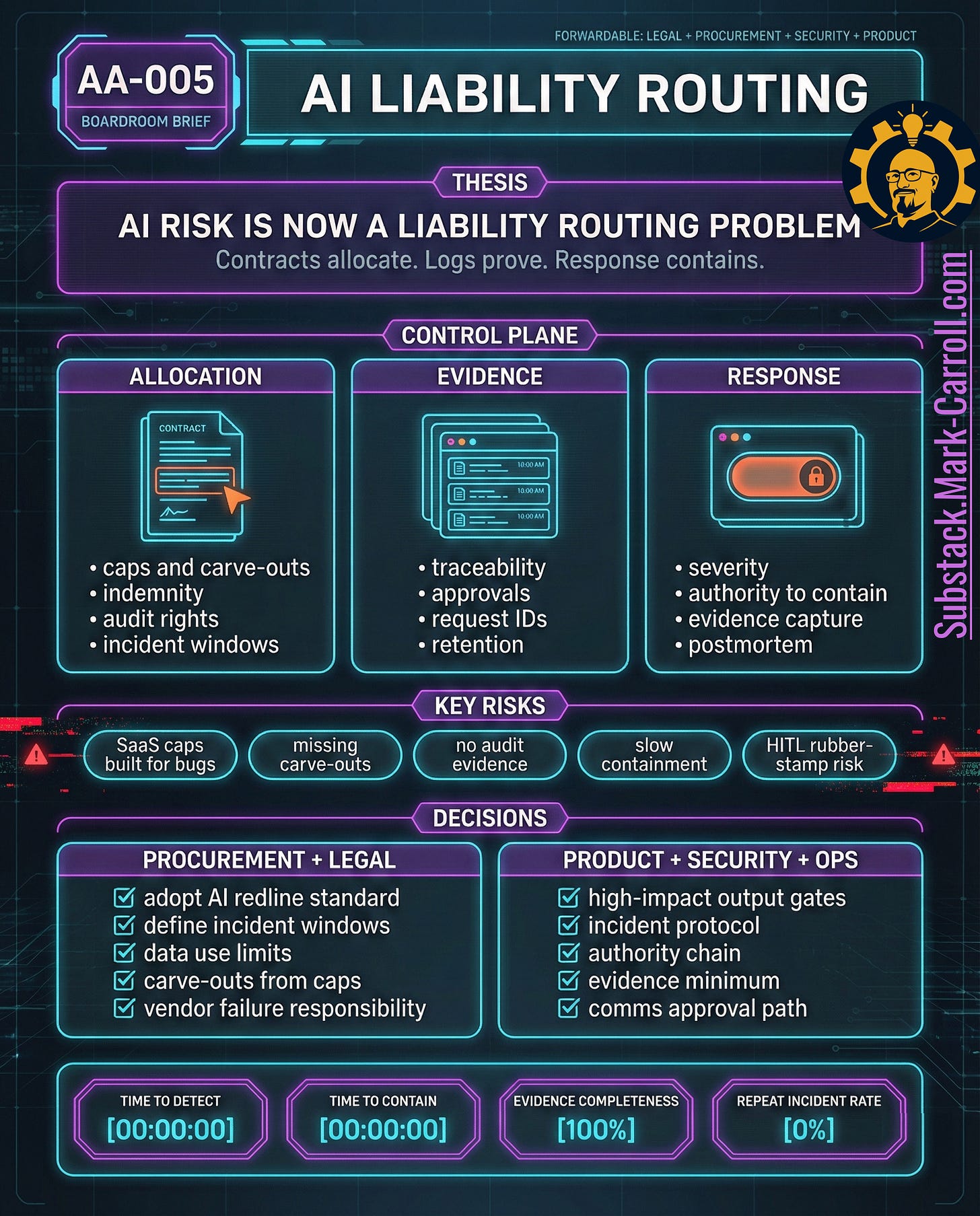

Boardroom One-Pager

AA-005 Manager’s AI Liability Kit · Who pays, who approves, who contains, and how fast

What changed

AI risk is no longer a model quality discussion. AI risk is now a liability routing problem.

If an AI system can make promises, change accounts, influence eligibility, or touch sensitive data, liability is determined by contract allocation, evidence, and incident discipline.

Three non-negotiables

Allocation: Contracts must address AI-specific failure modes and responsibilities. Standard SaaS language is not sufficient for autonomous behavior.

Evidence: Traceability is a legal survival requirement. Without reconstruction of actions and approvals, a decision cannot be defended.

Response: Incident response is a governance control. Time-to-containment and evidence completeness determine downstream cost.

Decisions this group must make

Procurement and Legal: Adopt a contract redline standard for AI vendors — audit rights, incident notification windows, data use limits, carve-outs from caps, explicit vendor responsibility.

Product: Define high-impact output gates for pricing, refunds, eligibility, account actions, and policy commitments. Require confirmation plus logging.

Security and Operations: Adopt an AI incident protocol that defines who declares severity, who contains, what evidence must be captured, who contacts vendor and legal, and who approves customer communications.

Success metrics

Time to detect. Time to contain. Evidence completeness score. Repeat incident rate per workflow.

Bottom line

Liability is not handled later. Liability is designed now — in contracts, gates, logs, and runbooks.

APPENDIX: Downloadable Materials

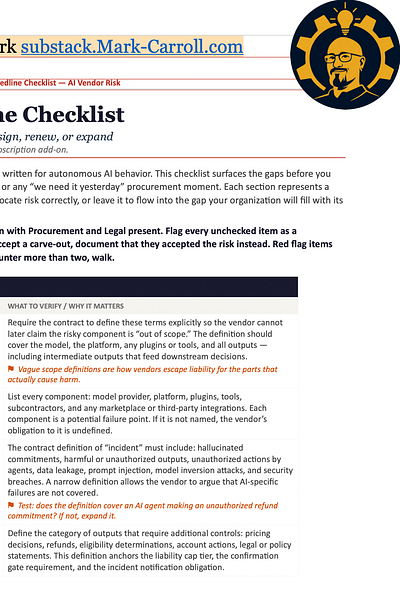

Download 01: Contract Redline Checklist (AI vendor risk)

Use before you sign, renew, or expand an AI vendor contract. Surprise liability stops being a subscription add-on.

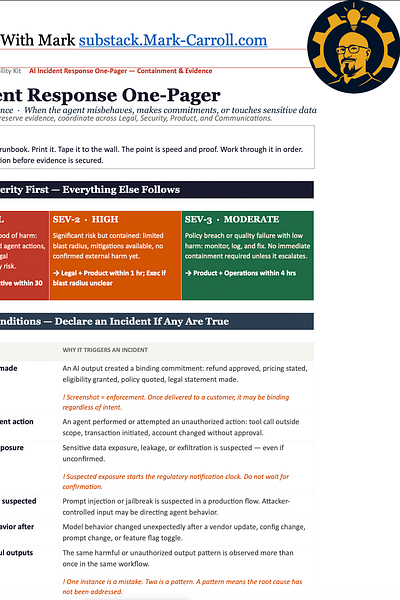

Download 02: AI Incident Response One-Pager (containment and evidence)

Use when the agent misbehaves, makes commitments, or touches sensitive data. Contain fast. Preserve evidence.

Use these two artifacts together. Redlines decide the blast radius. Incident response decides whether you can contain and prove.

Reader Question

Where have you seen liability show up before anyone expected it. When it did, did your organization have authority, evidence, and protocol. Or did you have a meeting to decide who should have been responsible.

The filing stays abstract.

The contract decides who bleeds.

The bill does not.

Next: AA-006, The Standards War — whose standard becomes the default, who gets to certify compliance, and who gets blamed when standards collide.

If you’re building teams that need to move fast without breaking trust, that’s the same muscle in a different arena.

If an AI agent makes a promise that can be screenshot-ed and enforced today, whose name goes on the explanation tomorrow, and can you prove it with logs?